Piaget, Jean. Piaget, Jean Professional biography of Piaget

Last update: 05/01/2014

The theory developed by Jean Piaget back in the last century still enjoys the approval of many psychologists. What is so remarkable about his ideas?

According to the Swiss psychologist, children go through four main stages of cognitive development, each of which involves a significant change in their understanding of the world. Piaget believed that children - like “little scientists” - are actively trying to study and comprehend the world around them. Thanks to observations of his own children, Piaget developed a theory of human intellectual development, in which he distinguished the following stages:

- sensorimotor (from birth to 2 years);

- preoperative (from 2 to 7 years);

- stage of specific operations (from 7 to 11 years);

- the stage of formal operations (it begins in adolescence and covers the entire adult life of a person).

Prerequisites for the emergence of Jean Piaget's theory of cognitive development

Jean Piaget was born in 1896 in Neuchâtel (Switzerland). At the age of 22, Piaget received his PhD and began a long career that would have a profound impact on the development of psychology and education. Although Piaget was initially interested in biology (especially ornithology and malacology), after working with Alfred Binet, he became interested in psychology and, in particular, the intellectual development of children. Based on his observations, he came to the conclusion that Children are by no means dumber than adults - they just think differently. “It’s so simple that only a genius could have thought of it,” is how Albert Einstein responded to Jean Piaget’s discovery.

Piaget's stage theory describes the development of the intellectual sphere of children, which includes changes affecting the child's cognition and cognitive abilities. According to Piaget, cognitive development first involves action-based processes, and only then manifests itself in the form of changes in mental processes.

Briefly about cognitive development

Each of the four stages has its own characteristics in terms of changes occurring in the child’s intellectual sphere.

- . At this stage, children acquire knowledge through sensory experience and control of objects in the surrounding reality.

- . At this stage, children learn about the world through play. However, behind the seemingly simple process of the game there is a complex process of mastering logic and understanding the point of view of other people.

- . At this stage of development, children begin to think more logically, but their thinking still does not have the flexibility of adult thinking. They tend not to understand or accept abstract and hypothetical concepts.

- . The final stage of J. Piaget's theory involves the development of logic, the ability to use deductive reasoning and understand abstract ideas.

It is important to note that Piaget did not consider the process of mental development in children in a quantitative aspect - that is, as children get older, in his opinion, they do not simply accumulate information and knowledge. Instead, Piaget suggested that as these four stages are gradually overcome, a qualitative change in the child's way of thinking occurs. At the age of 7 years, a child does not have more information about the world compared to two years of age; the fundamental difference is in the way he thinks about the world.

Basic concepts of J. Piaget's theory

To better understand some of the processes that occur during cognitive development, it is important to first examine several important ideas and concepts introduced by Piaget. Below are some of the factors that influence children's learning and development.

- Action diagram. This concept describes both mental and physical activities associated with understanding and learning about the world around us. Schemas are categories of knowledge that help us interpret and understand the world. From Piaget's point of view, the schema includes both knowledge itself and the process of obtaining it. Once the child has new experiences, the new information is used to change, supplement, or replace the pre-existing schema. To illustrate this concept with an example, we can imagine a child who has a diagram about a certain type of animal - a dog, for example. If until now the child’s only experience has been acquaintance with small dogs, then he may believe that absolutely all small, furry four-legged animals are called dogs. Now suppose that a child encounters a very large dog. The child will perceive this new information by incorporating it into an already existing scheme.

- Assimilation. The process of incorporating new information into pre-existing schemas is known as assimilation. This process is somewhat subjective in nature, because we, as a rule, try to slightly change the new experience or information received in order to fit it into already formed beliefs. The child’s perception of the dog from the above example and, in fact, the definition of it as a “dog” is an example of the assimilation of the animal with the child’s schema of the dog.

- Accommodation. Adaptation also involves changing or replacing existing schemas in the light of new information - that is, a process known as accommodation. It involves the very change of existing patterns or ideas as a result of the emergence of new information or new impressions. During this process, completely new schemes can be developed.

- Balancing. Piaget believed that all children try to find a balance between assimilation and accommodation - this is achieved precisely through a mechanism called equilibration by Piaget. As we progress through the stages of cognitive development, it is important to maintain a balance between applying pre-formed knowledge (i.e., assimilation) and changing behavior in response to new information (accommodation). Balancing helps explain how children are able to move from one stage of thinking to another.

Preface to the first edition

A book entitled "The Psychology of Intelligence" could cover a good half of the entire subject of psychology. But on the pages of this book the author will limit himself to outlining one general concept, namely the concept of the formation of “operations”, and will show, perhaps more objectively, its place among other concepts accepted in psychology. First, we will talk about characterizing the role of the intellect in its relation to adaptive processes as a whole (Chapter I), then, considering the “psychology of thinking,” we will show that the activity of the intellect consists, essentially, in “grouping » operations in accordance with defined structures (Chapter II). The psychology of intelligence, understood as a special form of balance to which all cognitive processes gravitate, poses such problems as the relationship between intelligence and perception (Chapter III), intelligence and skill (Chapter IV), as well as questions of the development of intelligence (Chapter V) and its socialization (Chapter VI).

Despite the abundance of valuable work in this area, the psychological theory of intellectual mechanisms is still emerging, and so far one can only vaguely guess what degree of accuracy it will have. Hence the feeling of searching that I tried to express here.

This little book sets out the most essential parts of a course of lectures which I had the honor of delivering to the Collège de France in 1942, at a time when all the university teachers were striving, in the face of violence, to express their solidarity and their fidelity to enduring values. In preparing this book, I cannot forget the reception given to me by my audience of those years, as well as the contacts that I had with my teacher P. Janet and with my friends A. Pieron, A. Vallon, P. Ginome, G. . Bachelenrom, P. Masson-Ourselem. M. Mauss and many others, not to mention my dear I. Meyerson, who “resisted” in a completely different place.

Preface to the second edition

The reception given to this little work was generally quite favorable, which prompted us to republish it without changes. At the same time, many critical comments have been made about our concept of intelligence due to the fact that it is associated with higher nervous activity and the process of its formation in ontogenesis. It seems to us that this reproach is based on a simple misunderstanding. Both the concept of “assimilation” and the transition from rhythmic actions to regulations, and from them to reversible controls, require neurophysiological, and at the same time psychological (and logical) interpretations. Far from being contradictory, these two interpretations can ultimately be reconciled. Elsewhere we will dwell on this essential point, but in no case do we consider ourselves entitled to begin to resolve this issue until detailed psychogenetic research has been completed, of which this little book is a summary.

October 1948

PART ONE. THE NATURE OF INTELLIGENCE

Chapter 1. Intelligence and biological adaptation.

Every psychological explanation sooner or later ends up relying on biology or logic (or sociology, although the latter itself ultimately faces the same alternative). For some researchers, mental phenomena are understandable only when they are associated with a biological organism. This approach is quite applicable when studying elementary mental functions (perception, motor function, etc.), on which intelligence depends at its origins. But it is not at all clear how neurophysiology will ever be able to explain why 2 and 2 make 4, or why the laws of deduction are necessarily imposed on the activities of consciousness. Hence another tendency, which is to consider logical and mathematical relations as irreducible to any Others and to use them for the analysis of higher intellectual functions. It remains only to resolve the question: can logic itself, understood as something going beyond the limits of experimental psychological explanation, nevertheless serve as the basis for interpreting the data of psychological experience as such? Formal logic, or logistics, is an axiomatics of states of equilibrium of thinking, and the real science corresponding to this axiomatics can only be the psychology of thinking. With such a formulation of problems, the psychology of intelligence must, of course, take into account all the achievements of logic, but the latter in no way can dictate to the psychologist his own decisions: logic is limited only to what poses problems for the psychologist.

The dual nature of intelligence, both logical and biological, is what we should start from. The following two chapters are intended to outline these preliminary questions and, above all, to show to the maximum extent the unity (as far as possible in the modern state of knowledge) of these two, at first glance irreducible to each other, fundamental aspects of the life of thought.

The place of intelligence in mental organization

Any behavior, whether we are talking about action unfolding externally, or about internalized action in thinking, acts as an adaptation, or, better said, as readaptation. An individual acts only if he feels the need for action, i.e. if for a short time there is an imbalance between the environment and the organism, and then the action is aimed at re-establishing this balance, or, more precisely, at readapting the organism (Claparsd). Thus, “behavior” is a special case of exchange (interaction) between the external world and the subject. But in contrast to physiological exchanges, which are material in nature and involve internal changes in bodies, the “behaviors” studied by psychology are functional in nature and are realized over long distances - in space (perception, etc.) and in time (memory, etc. .), as well as along very complex trajectories (with bends, deviations, etc.). Behavior, understood in the sense of functional exchanges, in turn, presupposes the existence of two important and closely related aspects: affective and cognitive.

The relationship between affect and knowledge has been the subject of much debate. According to P. Janet, one should distinguish between the “primary action”, or the relationship between the subject and the object (intelligence, etc.), and the “secondary action”, or the reaction of the subject to his own action: this reaction, which forms elementary feelings, consists of regulation of primary actions and provides an outlet for excess internal energy. However, it seems to us that along with regulations of this kind, which essentially determine the energy balance or internal economy of behavior, there should be a place for such regulations that would determine the finality of behavior and establish its values. And it is precisely these values that should characterize the energy or economic exchange of a subject with the external environment. According to Clarapède, the senses prescribe a goal to behavior, while the intellect is limited to providing behavior with the means ("technique"). But there is also an understanding in which goals are viewed as means and in which the finality of the action is constantly changing. Since feeling to some extent guides behavior by assigning value to its goals, the psychologist should limit himself to stating the fact that it is feeling that gives action the necessary energy, while knowledge imposes a certain structure on behavior. This gives rise to the solution proposed by the so-called “psychology of form”: behavior is a “complete field” that embraces both subject and object; the dynamics of this field are formed by feelings (Lewin), while its structuring is provided by perception, motor function and intellect. We are ready to agree with this formulation with one clarification: both feelings and cognitive forms depend not only on the currently existing “field”, but also on the entire previous history of the acting subject. And in this regard, we would simply say that all behavior involves both an energetic or affective aspect and a structural or cognitive aspect, which, in our opinion, really unites the points of view outlined above.

Jean Piaget was born in Neuchâtel, the capital of the French-speaking canton of Neuchâtel in Switzerland. His father, Arthur Piaget, was a professor of medieval literature at the University of Neuchâtel. Piaget began his long scientific career at the age of ten, when he published a short note on albino sparrows in 1907. During his scientific life, Piaget wrote more than 60 books and several hundred articles.

Piaget became interested in biology early, especially mollusks, and published several scientific papers before finishing school. As a result, he was even offered the prestigious position of caretaker of the mollusk collection at the Geneva Museum of Natural History. By the age of 20, he had become a recognized malacologist.

Piaget completed his PhD in natural sciences at the University of Neuchâtel, and he also studied for a time at the University of Zurich. At this time, he began to get involved in psychoanalysis, a very popular direction of psychological thought at that time.

After receiving his degree, Piaget moved from Switzerland to Paris, where he taught at a boys' school on the Rue Grande aux Velles, whose director was Alfred Binet, the creator of the IQ test. While helping to process IQ test results, Piaget noticed that young children consistently gave incorrect answers to some questions. However, he focused less on the wrong answers and more on the fact that children make the same mistakes that older people do not. This observation led Piaget to theorize that the thoughts and cognitive processes of children differ significantly from those of adults. He went on to create a general theory of developmental stages, which states that people at the same stage of their development exhibit similar general forms of cognitive abilities. In 1921, Piaget returned to Switzerland and became director of the Rousseau Institute in Geneva.

In 1923, Piaget married Valentine Chatenau, who was his student. The married couple had three children, whom Piaget studied since childhood. In 1929, Piaget accepted an invitation to take up the post of director of the International Bureau of Education, which he remained at the head of until 1968.

Scientific heritage

Peculiarities of the child's psyche

In the initial period of his work, Piaget described the features of children’s ideas about the world:

- inseparability of the world and one’s own self,

- animism (belief in the existence of souls and spirits and in the animation of all nature),

- Artificialism (perception of the world as created by human hands).

To explain them, I used the concept of egocentrism, by which I understood a certain position in relation to the surrounding world, overcome through the process of socialization and influencing the constructions of children's logic: syncretism (connecting everything with everything), non-perception of contradictions, ignoring the general when analyzing the particular, misunderstanding the relativity of some concepts. All these phenomena find their most vivid expression in egocentric speech.

Theory of intelligence

Subsequently, J. Piaget turned to the study of intelligence, in which he saw the result of the internalization of external actions.

Stages of intelligence development

Piaget identified the following stages of intelligence development.

During the period of sensorimotor intelligence, the organization of perceptual and motor interactions with the outside world gradually develops. This development goes from being limited by innate reflexes to the associated organization of sensorimotor actions in relation to the immediate environment. At this stage, only direct manipulations with things are possible, but not actions with symbols and ideas on the internal plane.

At the stage of pre-operational representations, a transition occurs from sensorimotor functions to internal - symbolic ones, that is, to actions with representations, and not with external objects.

This stage of intellectual development is characterized by the dominance of preconcepts and transductive reasoning; egocentrism; focusing on a striking feature of an object and neglecting its other features in reasoning; focusing on the states of a thing and not paying attention to its transformations.

At the stage of concrete operations, actions with representations begin to be combined and coordinated with each other, forming systems of integrated actions called operations. The child develops special cognitive structures called groupings (for example, classification), thanks to which the child acquires the ability to perform operations with classes and establish logical relationships between classes, uniting them in hierarchies, whereas previously his capabilities were limited to transduction and the establishment of associative connections.

The limitation of this stage is that operations can only be performed with specific objects, but not with statements. Operations logically structure the external actions performed, but they cannot yet structure verbal reasoning in the same way.

The main ability that appears at the stage of formal operations (from 11 to approximately 15 years old) is the ability to deal with the possible, with the hypothetical, and to perceive external reality as a special case of what is possible, what could be. Cognition becomes hypothetico-deductive. The child acquires the ability to think in sentences and establish formal relationships (inclusion, conjunction, disjunction, etc.) between them. A child at this stage is also able to systematically identify all the variables essential to solving a problem and systematically go through all possible combinations of these variables.

Language and thinking

Regarding the relationship between language and thinking in cognitive development, Piaget believes that “language does not fully explain thinking, since the structures that characterize this latter are rooted in action and in sensorimotor mechanisms deeper than linguistic reality. But it is still obvious that the more complex the structures of thought become, the more necessary language is to complete their processing. Consequently, language is a necessary, but not sufficient condition for the construction of logical operations."

Criticism of J. Piaget in Russian psychology

In the book “Thinking and Speech” (1934), L. S. Vygotsky entered into a correspondence discussion with Piaget on the issue of egocentric speech. Considering Piaget's work as a major contribution to the development of psychological science, L. S. Vygotsky reproached him for the fact that Piaget approached the analysis of the development of higher mental functions abstractly, without taking into account the social and cultural environment. Unfortunately, Piaget was able to become acquainted with Vygotsky's views only many years after Vygotsky's early death.

Differences in the views of Piaget and domestic psychologists are manifested in the understanding of the source and driving forces of mental development. Piaget viewed mental development as a spontaneous process, independent of learning, that obeys biological laws. Domestic psychologists see the source of a child’s mental development in his environment, and development itself is viewed as a process of the child’s appropriation of socio-historical experience. This explains the role of learning in mental development, which is especially emphasized by domestic psychologists and underestimated by Piaget. Critically analyzing the operational concept of intelligence proposed by Piaget, domestic experts do not consider logic as the only and main criterion of intelligence and do not evaluate the level of formal operations as the highest level of development of intellectual activity. Experimental studies (Zaporozhets A.V., Galperin P.Ya., Elkonin D.B.) showed that not logical operations, but orientation in objects and phenomena is the most important part of any human activity and the results of this activity depend on its nature.

PIAGE JEAN.

Jean Piaget was born on August 9, 1896 in the Swiss city of Neuchatel. As a child, he was consistently interested in mechanics, birds, fossil animals and sea shells. His first scientific article was published when the author was only ten years old - these were observations of an albino sparrow seen while walking in a public park.

Also in 1906, Jean Piaget managed to get a job as a laboratory assistant at the Museum of Natural History with a specialist in mollusks. He worked there after high school for four years. During this time, 25 of his articles on malacology (the science of mollusks) and related issues of zoology were published in various journals. Based on these works, he was even offered the position of curator of the mollusk collection, however, when it turned out that the applicant for the position was still in high school, the offer was immediately withdrawn.

After graduating from school, Piaget entered the University of Neuchâtel, where he received a bachelor's degree in 1915 and a doctorate in natural sciences in 1918. During his studies, he read many books on biology, psychology, as well as philosophy, sociology and religion.

After graduating from university, Jean Piaget left the city and traveled for some time, stopping briefly in different places. Thus, he worked in the laboratory of Reschner and Lipps, at the Bleuer psychiatric clinic, and also at the Sorbonne. Finally, in 1919, he received an offer to work in Binet's laboratory at the École Supérieure de Paris, tasked with processing standardized reasoning tests completed by children. At first Piaget found this kind of work boring, but gradually he became interested and whoosh! participate in the research yourself. Having somewhat modified the method of psychiatric examination that he learned at the Bleuer clinic, Piaget soon began to successfully use the “clinical method.” He presented the results of his research in four articles published in 1921.

Initially, Piaget's clinical method developed as a reaction to the psychological test procedure. The test methodology was based on assessing the number of correct answers, but Piaget believed that erroneous judgments were the most important, because It is they who “give out” those patterns that are characteristic of children's thinking. At the same time, the process of studying intellectual activity no longer looks like a dispassionate recording of the child’s actions and judgments, but like an interaction between the subject and the experimenter, during which the latter draws certain conclusions.

In the same year, Piaget received an invitation to take the position of scientific director at the Jean-Jacques Rousseau Institute in Geneva. He agreed and devoted the next two years of his life to the study of child psychology: the characteristics of children's speech, the causal thinking of children, their ideas about everyday events, morality and natural phenomena. Based on experiments, he concluded about the innate egocentrism of the child and about his gradual socialization in the process of communicating with adults.

Speaking about socialization, Piaget eventually comes to the conclusion that social factors must be determined psychologically. Social life, in his opinion, cannot be considered as a whole in its relation to the psyche; instead, a number of specific social relations must be considered. Piaget introduced a psychological factor into the content of these relationships - the level of mental development of interacting individuals.

In 1923-1924, Piaget made an attempt to connect the structure of the unconscious thinking of an adult and the conscious thinking of a child. When interpreting children's myths, he used Freud's conclusions, but as his own ideas developed, he began to use psychoanalysis less and less.

Piaget was invited to teach at the University of Neuchâtel, he agreed, and from 1923 to 1929 he worked in two educational institutions simultaneously, constantly moving from Geneva to Neuchâtel and back. At the same time, he did not give up his scientific work. At

With the active participation of his wife Valentina Chatenais, Piaget conducted experiments with his own small children, studying their reaction to changing the shape of a piece of clay with a constant weight and volume.

The results obtained inspired him to conduct experiments with school-age children, during which he discovered a shift towards the use of tasks not only of a verbal nature. Nevertheless, Piaget did not give up experiments with his children, observing their behavior and reactions to external stimuli. At the same time, he completed his developments in the field of malacology.

By this period, Jean Piaget had developed certain views on the relationship of living organisms with the environment. Approaching this problem from a psychological point of view, Piaget does not ignore biological factors.

In 1929, Jean Piaget stopped teaching at the University of Neuchâtel and devoted himself entirely to work at the Institute of Jean-Jacques Rousseau. At this time, he was busy applying his own theory of the intellectual development of children in infancy to the creation and substantiation of pedagogical methods.

Piaget devoted the next ten years of his life to developing such a field of knowledge as genetic epistemology. Epistemology, or the theory of knowledge, studies knowledge from the point of view of the interaction of subject and object. Previous attempts at epistemology started from a static point of view, but Piaget believed that only a genetic and historical-critical approach could lead to a scientific epistemology. In his opinion, genetic epistemology should develop questions of methodology and theory of knowledge, based on the results of experimental mental research and the facts of the history of scientific thought. In addition, Piaget's epistemology made extensive use of logical and mathematical methods. This large-scale study culminates in a three-volume work, “Introduction to Genetic Epistemology” (Volume 1, “Mathematical Thought,” Volume 2, “Physical Thought,” and Volume 3, “Biological, Psychological and Social Thought”).

In 1941, Piaget stopped all his experiments with infants, his research now concerned the intellectual development of older children. He studied such images of cognitive activity in children as number and quantity, movement, time and speed, space, measurement, probability and logic. The logical-algebraic models constructed by Piaget were used by many famous psychiatrists of that time in their research.

At this time, he identified the main stages of child intelligence. At the age of two years, the child’s sensorimotor activity has not yet become completely reversible, but this trend is already visible. This is expressed, for example, in the fact that a child, traveling around the room, is able to return to the place from which his journey began.

Jean Piaget called the intelligence of children aged 2 to 7 years pre-operative. At this time, children form speech, as well as their own ideas about surrounding objects, image and word as a method of cognition replace movement, and “intuitive”, imaginative thinking develops. After this and until the age of 12, the child’s intellect goes through the stage of concrete operations. From mental actions, operations are formed that are already fully reversible and are performed only on real objects.

The last stage of the formation of intelligence is the stage of formal operations. The child develops the ability for hypothetical-deductive thinking, which no longer depends on specific actions.

From 1942, Jean Piaget lived in Paris, where he lectured, and after the end of the Second World War he moved to Manchester. At this time he received honorary titles from the universities of Harvard, Brussels, and the Sorbonne. In search of a method for testing the intellectual abilities of mentally retarded children, Piaget turned to quantity problems as the most universal. Also in Paris, the scientist continued to develop genetic epistemology and published several publications on this topic. In 1955, with a grant from the Rockefeller Foundation, Piaget founded the International Center for Genetic Epistemology.

Jean Piaget died on September 16, 1980 in Geneva. His contribution to modern science is enormous. Piaget's developments in the field of child psychology are still used by psychologists and teachers around the world. Thanks to the new science he created - genetic epistemology, the name of this Swiss psychologist, philosopher and logician is known throughout the world.

Biography

Jean Piaget was born in the city of Neuchâtel, the capital of the French-speaking canton of Neuchâtel in Switzerland. His father, Arthur Piaget, was a professor of medieval literature at the University of Neuchâtel, and his mother, Rebecca Jackson, was from France. Piaget began his long scientific career at the age of eleven, when he published a short note on albino sparrows in 1907. During his scientific life, Piaget wrote more than 60 books and several hundred articles.

Piaget became interested in biology early, especially mollusks, and published several scientific papers before finishing school. As a result, he was even offered the prestigious position of caretaker of the mollusk collection at the Geneva Museum of Natural History. By the age of 20, he had become a recognized malacologist.

When Jean Piaget was 15, his former nanny wrote a letter to his parents apologizing for her lies about saving their child from kidnapping. Afterwards, Piaget was surprised and delighted by how his mind projected a memory of an event that actually did not happen.

In 1918, Piaget defended his dissertation in natural sciences and received a PhD from the University of Neuchâtel, and he also studied for some time at the University of Zurich. During his studies, the scientist wrote two works on philosophy, but later he rejected them, considering them only the thoughts of a teenager. Also at this time, he began to get involved in psychoanalysis, a very popular direction of psychological thought at that time.

After receiving his degree, Piaget moved from Switzerland to Paris, where he taught at a boys' school on the Rue Grande-aux-Velles, whose director was Alfred Binet, the creator of the test. While helping to process IQ test results, Piaget noticed that young children consistently gave incorrect answers to some questions. However, he focused less on the wrong answers and more on the fact that children make the same mistakes that older people do not. This observation led Piaget to theorize that the thoughts and cognitive processes of children differ significantly from those of adults. He went on to create a general theory of developmental stages, which states that people at the same stage of their development exhibit similar general forms of cognitive abilities. In 1921, Piaget returned to Switzerland and became director in Geneva.

Every year he composed speeches for the IBE Council and the International Conference on Public Education, and in 1934 Piaget declared that “only education can save our society from possible collapse, immediate or gradual.”

From 1955 to 1980 he was director of the International Center for Genetic Epistemology. In 1964, Piaget was invited to speak as chief consultant at two conferences at Cornell University and the University of California at Berkeley. The conferences discussed the relationship between cognitive research and curriculum development.

In 1979, the scientist was awarded the Balzan Prize for Social and Political Sciences.

Jean Piaget died in 1980 and was buried, according to his request, with his family in Geneva.

Scientific heritage

Peculiarities of the child's psyche

Main article: J. Piaget's early concept of the development of a child's thinkingIn the initial period of his work, Piaget described the features of children’s ideas about the world:

- inseparability of the world and one’s own self,

- animism (belief in the existence of souls and spirits and in the animation of all nature),

- Artificialism (perception of the world as created by human hands).

To explain them, I used the concept of egocentrism, by which I understood a certain position in relation to the surrounding world, overcome through the process of socialization and influencing the constructions of children's logic: syncretism (connecting everything with everything), non-perception of contradictions, ignoring the general when analyzing the particular, misunderstanding the relativity of some concepts. All these phenomena find their most vivid expression in egocentric speech.

Theory of intelligence

In traditional psychology, children's thinking was considered more primitive compared to the thinking of an adult. But, according to Piaget, a child’s thinking can be characterized as qualitatively different, original and distinctively special in its properties.

Piaget developed his own method when working with children - a method of collecting data through a clinical conversation, during which the experimenter asks the child questions or offers certain tasks, and receives answers in free form. The purpose of the clinical interview is to identify the causes leading to the occurrence of symptoms.

The adaptive nature of intelligence

The development of intelligence occurs due to the subject's adaptation to a changing environment. Piaget introduced the concept of balance as the main life goal of the individual. The source of knowledge is the subject’s activity aimed at restoring homeostasis. The balance between the influence of the organism on the environment and the reverse influence of the environment is ensured by adaptation, that is, the balancing of the subject with the environment occurs on the basis of the balance of two differently directed processes - assimilation and accommodation. On the one hand, the action of the subject affects the objects surrounding him, and on the other, the environment influences the subject with a reverse effect.

Development of intelligence structures

Operations are internalized mental actions, coordinated into a system with other actions and possessing reversibility properties, which ensure the preservation of the basic properties of the object.

Piaget describes intellectual development in the form of various groupings, similar to mathematical groups. Grouping is a closed and reversible system in which all operations combined into a whole are subject to 5 criteria:

- Combination: A + B = C

- Reversibility: C - B = A

- Associativity: (A + B) + C = A + (B + C)

- General operation identity: A - A = 0

- Tautology: A + A = A.

Development of a child's thinking

Main article: J. Piaget's early concept of the development of a child's thinking- innately

- subject to the pleasure principle

- not directed to the outside world,

- does not adapt to external conditions.

Egocentric thinking occupies an intermediate stage between autistic logic and socialized, rational logic. The transition to egocentric thinking is associated with relationships of coercion - the child begins to correlate the principles of pleasure and reality.

Egocentric thought remains autistic in structure, but in this case the child’s interests are not aimed exclusively at satisfying organic needs or the needs of play, as is the case with autistic thought, but are also aimed at mental adaptation, which, in turn, is similar to the thought of an adult .

Piaget believed that the stages of development of thinking are reflected through an increase in the coefficient of egocentric speech (coefficient of egocentric speech = the ratio of egocentric utterances to the total number of utterances). According to the theory of J. Piaget, egocentric speech does not perform a communicative function; for the child, only interest on the part of the interlocutor is important, but he does not try to take the side of the interlocutor. From 3 to 5 years, the coefficient of egocentric speech increases, then it decreases, until about 12 years.

At the age of 7-12, egocentrism is displaced from the sphere of perception.

Characteristics of socialized thinking:

- subject to the principle of reality,

- is formed intravitally,

- aimed at understanding and transforming the external world,

- expressed in speech.

Types of speech

Main article: J. Piaget's early concept of the development of a child's thinkingPiaget divides children's speech into two large groups: egocentric speech and socialized speech.

Egocentric speech, according to J. Piaget, is such because the child speaks only about himself, without trying to take the place of the interlocutor. The child has no goal to influence the interlocutor, to convey to him some thought or idea; only the visible interest of the interlocutor is important.

J. Piaget divides egocentric speech into three categories: monologue, repetition and “monologue together.”

The increase in the coefficient of egocentric speech occurs from 3 to 5 years, but after, regardless of the environment and external factors, the coefficient of egocentric speech begins to decrease. Thus, egocentrism gives way to decentration, and egocentric speech gives way to socialized speech. Socialized speech, in contrast to egocentric speech, performs a specific function of message and communicative influence.

The sequence of development of speech and thinking, according to the theory of J. Piaget, is in the following sequence: first, non-speech autistic thinking appears, which is replaced by egocentric speech and egocentric thinking, after the “withering away” of which socialized speech and logical thinking are born.

Stages of intelligence development

Main article: Stages of development of intelligence (J. Piaget)Piaget identified the following stages of intelligence development.

Sensorimotor intelligence (0-2 years)

From the name it is clear that this type of intelligence concerns the sensory and motor areas. During this period, children discover the connection between their actions and their consequences. With the help of senses and motor skills, the child explores the world around him, every day his ideas about objects and objects improve and expand. The child begins to use the simplest actions, but gradually moves on to using more complex actions.

Through countless “experiments,” the child begins to form a concept of himself as something separate from the outside world. At this stage, only direct manipulations with things are possible, but not actions with symbols and representations on the internal plane. During the period of sensorimotor intelligence, the organization of perceptual and motor interactions with the outside world gradually develops. This development goes from being limited by innate reflexes to the associated organization of sensorimotor actions in relation to the immediate environment.

Preparation and organization of specific operations (2-11 years)

Sub-period of pre-operational ideas (2-7 years)

At the stage of pre-operational representations, a transition occurs from sensorimotor functions to internal - symbolic ones, that is, to actions with representations, and not with external objects. One symbol represents a specific entity that can symbolize another. For example, while playing, a child can use a box as if it were a table; pieces of paper can be plates for him. The child's thinking is still egocentric, he is hardly ready to accept the point of view of another person.

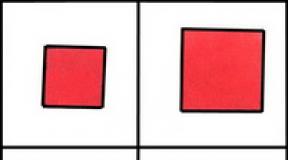

Play at this stage is characterized by decontextualization and the replacement of objects representing other objects. The child's delayed imitation and speech also reveal the possibilities of using symbols. Despite the fact that children 3-4 years old can think symbolically, their words and images do not yet have a logical organization. This stage is called pre-operational by Piaget, since the child does not yet understand certain rules or operations. For example, if you pour water from a tall and narrow glass into a short and wide one, the amount of water will not change - and adults know this, they can perform this operation in their minds and imagine the process. In a child at the preoperational stage of cognitive development, the concept of reversibility and other mental operations is rather weak or absent.

Another key characteristic of the pre-operational stage of a child’s thinking is egocentrism. It is difficult for a child at this stage of development to understand someone else’s point of view; they believe that everyone else perceives the world around them the same way as they do.

Piaget believed that egocentrism explains the rigidity of thinking at the pre-operational stage. Since a small child cannot appreciate another's point of view, he is therefore unable to revise his ideas, taking into account changes in the environment. Hence their inability to perform inverse operations or take into account conservation of quantity.

Sub-period of specific operations (7-11 years)

At this stage, mistakes that the child makes at the pre-operational stage are corrected, but they are corrected in different ways and not all at once.

From the name of this stage it becomes clear that we will talk about operations, namely logical operations and principles that are used to solve problems. A child at this stage is not only able to use symbols, but he can also manipulate them on a logical level. The meaning of the definition of “concrete” operation, which is included in the name of this stage, is that the operational solution of problems (i.e., a solution based on reversible mental actions) occurs separately for each problem and depends on its content. For example, physical concepts are acquired by a child in the following sequence: quantity, length and mass, area, weight, time and volume.

An important achievement of this period is mastering the concept of reversibility, that is, the child begins to understand that the consequences of one operation can be undone by performing a reverse operation.

At about 7-8 years old, a child masters the concept of conservation of matter, for example, he understands that if you make many small balls from a ball of plasticine, the amount of plasticine will not change.

At the stage of concrete operations, actions with representations begin to unite and coordinate with each other, forming systems of integrated actions called operations. The child develops special cognitive structures called factions(For example, classification), thanks to which the child acquires the ability to perform operations with classes and establish logical relationships between classes, uniting them in hierarchies, whereas previously his capabilities were limited to transduction and the establishment of associative connections.

The limitation of this stage is that operations can only be performed with specific objects, but not with statements. Operations logically structure the external actions performed, but they cannot yet structure verbal reasoning in the same way.

Formal Operations (11-15 years)

A child at the concrete operations stage faces difficulty in applying his abilities to abstract situations, that is, situations that are not represented in his life. If an adult said, “Don't tease that boy because he has freckles. Would you like to be treated like that?” the child's response would be, “But I don't have freckles, so no one will tease me!” "

It is too difficult for a child at the stage of concrete operations to realize an abstract reality that is different from his reality. A child at this stage can invent situations and imagine objects that do not exist in reality.

The main ability that emerges during the formal operations stage (from about 11 to about 15 years of age) is the ability to deal with possible, with the hypothetical, and perceive external reality as a special case of what is possible, what could be. Cognition becomes hypothetico-deductive. The child acquires the ability to think in sentences and establish formal relationships (inclusion, conjunction, disjunction, etc.) between them. A child at this stage is also able to systematically identify all the variables essential to solving a problem and systematically go through all possible combinations these variables.

Language and thinking

In the book “Thinking and Speech” (1934), L. S. Vygotsky entered into a correspondence discussion with Piaget on the issue of egocentric speech. Considering Piaget's work as a major contribution to the development of psychological science, L. S. Vygotsky reproached him for the fact that Piaget approached the analysis of the development of higher mental functions abstractly, without taking into account the social and cultural environment. Unfortunately, Piaget was able to become acquainted with Vygotsky's views only many years after Vygotsky's early death.

Differences in the views of Piaget and a number of Soviet psychologists are manifested in the understanding of the source and driving forces of mental development. Piaget viewed mental development as a spontaneous process, independent of learning, that obeys biological laws. Soviet psychologists saw the source of a child’s mental development in his environment, and development itself was viewed as a process of the child’s appropriation of socio-historical experience. This explains the role of learning in mental development, which was especially emphasized by domestic psychologists of the Soviet period and which, in their opinion, was underestimated by Piaget. Critically analyzing the operational concept of intelligence proposed by Piaget, Soviet specialists did not consider logic as the only and main criterion of intelligence and did not evaluate the level of formal operations as the highest level of development of intellectual activity. Experimental studies (Zaporozhets A.V., Galperin P.Ya., Elkonin D.B.) have shown that not logical operations, but orientation in objects and phenomena is the most important part of any human activity and the results of this activity depend on its nature. [ ]

Read also...

- Tasks for children to find an extra object

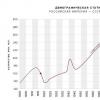

- Population of the USSR by year: population censuses and demographic processes All-Union Population Census 1939

- Speech material for automating the sound P in sound combinations -DR-, -TR- in syllables, words, sentences and verses

- The following word games Exercise the fourth extra goal