People are the same or... Are all people the same?

People's brains are very different - in their structure, architectonics, brain fields - the difference is 40 times. 40 times! This is the difference between a cockroach and a giant.

We think that all skeletons are the same, which means that all people are approximately the same. In fact, there is a big difference in the brain. And this is fundamental. Plus, there is also an age factor: after 55 years, apoptosis begins - this is the process of death of brain cells. If we add to the problems at birth the problems of apoptosis, plus insanity from the ideology that was drummed into us and which acted on a weak brain... then we get a charming picture of fanaticism - blind faith. And it doesn’t matter whether it’s faith in Stalin or whether it’s a terrorist who commits his act in the name of Allah, but it will be a completely sincere person. And the weaker a person’s brain, the more sincerity there is in a person. In the madhouse, everyone there is completely sincere people.

In general, people are, of course, not the same. Not every person is a highly developed personality.

Are all people the same? By the actions of people you will know their differences. We underestimate the animal that we beautifully and poetically call human. It contains so much disgusting and so much good, but these are all different people. There will be a lot of good in one person, and a lot of bad in another. There is no middle ground. The middle is not a common thing.

As a person seriously interested in physiology and neurophysiology, I will say that people are categorically different creatures. If some can not only kill, but kill brutally (for example, cut off a head) and do not experience any discomfort, no seminal lobes can prevent him from doing this. Well, his seminal lobes have not grown, or his metabolism is different (due to injury, illness), or something hereditary. And the other person is the opposite: the flower dies and tears are already welling up in his eyes. And when we show different examples (here a person suffers because of a flower, and here he chops off heads), and then we generalize it all and say - “here are people.” But the concepts of “man” and “humanity” cannot be generalized. There is a person and there is, as it were, a person. For me, at least, this is true. There is no one person for me. This is my point of view and I have the right to it.

From an evolutionary perspective, all human races are variations of the same gene pool. But if people are so similar to each other, why are human societies so different? T&P publishes science journalist Nicholas Wade's take on this paradox from the bestselling book An Inconvenient Inheritance. Genes, races and human history”, the translation of which was published by the Alpina Non-Fiction publishing house.

The main argument is this: these differences do not arise from some huge difference between individual representatives of the races. On the contrary, they are rooted in very small variations in the social behavior of people, for example, in the degree of trust or aggressiveness or in other character traits that developed in each race depending on geographical and historical conditions. These variations set the framework for the emergence of social institutions that differed significantly in character. Because of these institutions - largely cultural phenomena based on a foundation of genetically determined social behavior - the societies of the West and East Asia are so different from each other, tribal societies are so unlike modern states, and.

The explanation of almost all social scientists boils down to one thing: human societies differ only in culture. This implies that evolution played no role in the differences between populations. But explanations in the spirit of “it’s just culture” are untenable for a number of reasons.

First of all, this is just a guess. No one can currently say how much genetics and culture underlie the differences between human societies, and the claim that evolution plays no role is merely a hypothesis.

Second, the "it's only culture" position was formulated primarily by anthropologist Franz Boas to contrast it with racism; This is commendable from the point of view of motives, but there is no place in science for political ideology, no matter what kind it may be. Furthermore, Boas wrote his works at a time when human evolution was not known to have continued until the recent past.

Third, the “it's just culture” hypothesis does not provide a satisfactory explanation for why differences between human societies are so deeply rooted. If the differences between tribal society and the modern state were purely cultural, it would be quite easy to modernize tribal societies by adopting Western institutions. American experience with Haiti, Iraq and Afghanistan generally suggests that this is not the case. Culture undoubtedly explains many important differences between societies. But the question is whether such an explanation is sufficient for all such differences.

Fourthly, the assumption “this is only culture” is in dire need of adequate processing and adjustment. His successors failed to update these ideas to include the new discovery that human evolution continued into the recent past, was extensive, and was regional in nature. According to their hypothesis, which contradicts evidence accumulated over the past 30 years, the mind is a blank slate, formed from birth without any influence of genetically determined behavior. Moreover, the importance of social behavior, they believe, for survival is too insignificant to be the result of natural selection. But if such scientists accept that social behavior does have a genetic basis, they must explain how behavior could remain the same across all races despite massive shifts in human social structure over the past 15,000 years, while many other traits are now known to have evolved independently in each race, transforming at least 8% of the human genome.

“Human nature throughout the world is generally the same, except for slight differences in social behavior. These differences, although barely noticeable at the level of the individual, add up and form societies that are very different from each other in their qualities.”

The idea of [this] book suggests that, on the contrary, there is a genetic component to human social behavior; this component, very important for the survival of people, is subject to evolutionary changes and has indeed evolved over time. This evolution of social behavior has certainly occurred independently in the five major and other races, and small evolutionary differences in social behavior underlie differences in the social institutions prevailing in large human populations.

Like the “it's just culture” position, this idea is not yet proven, but rests on a number of assumptions that seem reasonable in light of recent knowledge.

First: the social structures of primates, including humans, are based on genetically determined behavior. Chimpanzees inherited the genetic template for the functioning of their characteristic societies from an ancestor that is common to humans and chimpanzees. This ancestor passed on the same pattern to the human lineage, which subsequently evolved to support traits specific to the social structure of humans from , which arose about 1.7 million years ago, to the emergence of hunter-gatherer groups and tribes. It is difficult to understand why humans, a highly social species, should have lost the genetic basis for the set of social behaviors on which their society depends, or why this basis should not have continued to evolve during the period of the most radical transformation, namely the change that allowed human societies to grow into ranging in size from a maximum of 150 people in a hunting-gathering group to huge cities containing tens of millions of inhabitants. It should be noted that this transformation must have developed independently in each race, since it occurred after their separation. […]

The second assumption is that this genetically determined social behavior supports the institutions around which human societies are built. If such forms of behavior exist, then it seems undeniable that institutions must depend on them. This hypothesis is supported by such reputable scientists as economist Douglas Northey and political scientist Francis Fukuyama: they both believe that institutions are based on the genetics of human behavior.

Third assumption: the evolution of social behavior has continued over the last 50,000 years and throughout historical time. This phase undoubtedly occurred independently and in parallel in the three main races after they had diverged and each had made the transition from hunting and gathering to sedentary life. Genomic evidence that human evolution has continued in the recent past, has been widespread and regional, generally supports this thesis, unless some reason can be found for social behavior to be free from the action of natural selection. […]

The fourth assumption is that advanced social behavior can in fact be observed in various modern populations. Behavioral changes historically documented for the English population during the 600-year period leading up to the Industrial Revolution include a decrease in violence and an increase in literacy, propensity to work and save. The same evolutionary changes appear to have occurred in other agrarian populations in Europe and East Asia before they entered their industrial revolutions. Another behavioral change is evident in the Jewish population, which has adapted over the centuries, first and then to specific professional niches.

The fifth assumption relates to the fact that significant differences exist between human societies, and not between their individual representatives. Human nature is generally the same throughout the world, with the exception of slight differences in social behavior. These differences, although subtle at the level of the individual, add up to form societies that are very different from each other in their qualities. Evolutionary differences between human societies help explain major turning points in history, such as China's construction of the first modern state, the rise of the West and the decline of the Islamic world and China, and the economic inequalities that have emerged in recent centuries.

To say that evolution has played some role in human history does not mean that this role is necessarily significant, much less decisive. Culture is a powerful force, and people are not slaves to innate inclinations, which can only direct the psyche one way or another. But if all individuals in a society have the same inclinations, albeit minor ones, for example, towards a greater or lesser level of social trust, then this society will be characterized by precisely this tendency and will differ from societies in which there is no such inclination.

One of the most interesting branches of psychology is personality psychology. Back in the late thirties, people actively began to conduct various studies on this topic. So by the second half of the last century, numerous approaches and theories about personality had been formed. Every person is different. Why are people so different?

We believe that the most appropriate definition is the following. Personality is the systemic stability of the social traits of an individual person, which characterizes the individual as a member of a particular society.

One of the most modern approaches considers personality as a biopsychosocial system. Actually, it is these three factors that make up personality - psychological, biological and social.

The biological factor includes all external signs (height, eye color, nail shape) and internal ones (parasympathetic and sympathetic types of the autonomic system, biorhythms, circulatory characteristics - in short, all those points that relate to anatomical and physiological characteristics).

The psychological factor includes all mental functions - attention, perception, memory, emotions, thinking, will. All these features have a material basis and are quite strongly determined by it, that is, they are determined in most cases genetically.

Well, the last factor includes the social factor. This factor is somewhat more difficult to explain, because it includes all communication, all interaction with the world and people around you. To put it simply, this is the entire life path and again of a person in general.

However, here you may ask, at what point does the formation of a person as a personality begin? After all, we all know that one is not born as an individual, one becomes one, and individuality is defended.

All people are born very similar, despite the fact that each baby has its own set of psychological and biological characteristics that rapidly develop in the first year of a child’s life. Over time, each child develops not only his own psychological characteristics, but also acquires social skills, experience communicating with others, and relationships. Time passes, and a person’s circle of contacts and acquaintances grows more and more, so that the experience of his communication becomes more and more multifaceted. This is how a personality is formed, and this is how the uniqueness of each individual person appears, because both life experiences and social circles of people are completely different. It is impossible to plan or calculate them, because in this matter there are too many random moments, phenomena, life circumstances that change every minute. Life experience is acquired by a person not only in connection with human communication, but also in connection with various social and personal events.

What happens to a person when he is sick? Initially, a person is born with one set of psychological and social qualities. So he lived, grew, developed, gained experience in various social spheres, and then suddenly fell ill. As a result of the disease, some of his biological characteristics changed (some part of his health was lost), as well as psychological characteristics (memory and thinking change - now the person begins to think about the disease and how to get rid of it). In addition, the disease also affects from the point of view of society, because society treats sick people somewhat differently than healthy ones. The duration of the illness also plays a role here - society reacts little to a short-term illness, but to a long-term illness, the attitude will be somewhat different. Here a person already gains experience of communicating, say, not at school, but in a hospital with other patients and representatives of adult society, doctors, and not teachers. Often this communication continues for quite a long time after recovery.

This is what we are talking about when we say that the experience of social communication and social life affects each person individually, which makes him one and only. Here is the answer to everyone’s question: why are all people different?

However, statements are often heard that all people are the same. What to do with this statement? Yes, it is true that a person does not change much even throughout his entire existence. According to Mr. Freud's psychoanalytic theory, a general principle of human psychological structure was deduced. Here we are talking about absolute hedonism, which states that people always strive for pleasure. That is why, since the existence of man, he has always sought to satisfy his main need - the need to receive complete pleasure. Of course, many here do not agree with these statements, which is why a little later this principle was somewhat refined and changed, and later it was called absolute hedonism. It now begins to sound like this: a person strives for a life full of pleasures and without conflicts. What is meant here is that in the constant search for pleasure, a person is constantly obliged to correlate his interests with the interests of society, with external circumstances, so that he must constantly maintain a balance between his own interests and the interests of the social environment.

The principle of hedonism is especially pronounced in the child’s psyche. Observing a little person for just one day, it immediately becomes clear that all his thoughts, interests and actions are aimed precisely at getting pleasure, in order to restore his inner comfort. However, children gradually become involved in the process of socialization, so that now the limiting factors that prevent him from constantly having pleasure become social ones. And the better, the more successful the socialization process is, the more adapted and autonomous the individual becomes. The universal guarantee of personal health, of every person (mental) is to be happy, but at the same time to live without conflicts.

Personality psychology is perhaps the most interesting section of psychology. Since the late 1930s. active research began in personality psychology. As a result, by the second half of the last century, many different approaches and theories of personality had developed. Currently, there are about 50 definitions of the concept of personality

Personality is a stable system of socially significant traits that characterize an individual as a member of a particular society.

The most modern approach considers a person as a biopsychosocial system. And, by and large, the totality of these three factors: biological, psychological and social is the personality.

The biological factor is external signs: eye color, height, and shape of nails; internal signs: sympathetic or parasympathetic type of the autonomic nervous system, features of blood circulation, biorhythms, in a word: a biological factor is everything that relates to human anatomy and physiology.

The psychological factor is all mental functions: perception, attention, memory, thinking, emotions, will, which are based on a material substrate and are largely conditioned by it, i.e. determined genetically.

And finally, the third component of personality is the social factor. What is meant by this social factor?

The social factor is, in principle, the entire experience of communication and interaction with people around us and with the world around us as a whole. Those. it is essentially the entire life experience of a person.

What do you think: at what point does personality formation begin?

I don’t remember who said it, but very precisely: “One is born an individual, one becomes an individual, and one defends individuality.”

People are born very similar. Of course, babies are different because each has its own individual set of biological qualities, as well as psychological ones, that will develop rapidly in the first years of life. And yet they are very similar to each other. Gradually, each person not only develops his psychological qualities, but also acquires social experience - the experience of relationships with the people around him. Gradually, a person grows up and the circle of people around him becomes wider, more diverse, and his communication experience becomes more and more versatile. This is how a personality is formed, this is how the uniqueness of each person multiplies, because everyone has their own life experience. It is impossible to plan and calculate, because too many random phenomena and circumstances interfere and integrate into the life of every person every day and every minute. Life experience is a social factor of the individual; it is formed not only on the basis of interaction with people, but also on the basis of interaction with various social and personal events.

For example, a person fell ill with a serious illness. What's happening? Here a person was born with a certain set of biological and psychological qualities, lived - developed - gained experience in social interactions and suddenly fell ill. An illness is an event that changes a biological factor - during the period of illness some part of his health was lost, the psychological factor also changed, since during an illness the state of all mental functions and memory, and attention, and thinking - in any case, the content of thinking - changes – now the person thinks about the disease and how to recover from it. The disease also affects the social factor. People around them treat a sick person differently than a healthy person. If the illness is short-lived, then its effect will be short and insignificant, but if we are talking about a severe and long-term illness. For example, a child is 7 years old and it’s time for him to go to school - this event is planned, at school he will communicate with peers and teachers, a lot will change in his life and he will intensively acquire new social experience. What if the illness is serious and treatment requires several months? And in this case, a person will acquire his own unique social experience, only this experience will be different in content. He will communicate with peers, but not at school, but in the hospital, and he will also communicate with authoritative adults, but not with teachers, but with representatives of the medical professions. In addition, his relationships with close people around him will also change. Moreover, sometimes these changes in relationships with the immediate environment can continue not only during the period of illness, but also for a long time after. This example is a particular one, but it will illustrate how variable and not always predictable the social experience of each person can be.

It is this social experience that gives each person uniqueness and makes him unique, one of a kind. This is the answer to the question: why are all people different?

On the other hand, we often say: people are all the same and even throughout their history of existence, people have not changed much. S. Freud, in the course of creating his psychoanalytic theory, deduced the general principle of the psychological structure of man - the principle of absolute hedonism, which means that a person constantly strives to receive pleasure. Based on this principle, the main need of a person and the main motivation for all his actions is to obtain pleasure. Many people do not agree with this formulation and are ready to argue. Subsequently, this principle was refined, slightly changed and received the name of the principle of relative hedonism, which sounds like this: a person strives to have pleasure and live without conflicts. Those. a person, in his desire to obtain pleasure, constantly correlates the satisfaction of his needs with external circumstances, wanting to maintain a balance between his interests - pleasures and the social environment. The principle of absolute hedonism is inherent in the child’s psyche. If you observe a small child during the day, it becomes obvious that all his thoughts, interests and actions are aimed precisely at obtaining pleasure and restoring a state of internal comfort. Gradually, the child becomes involved in the process of socialization and the main limiting factor preventing pleasure becomes social. The more successfully socialization is completed, the more autonomous and, at the same time, more adaptive the personality is formed. Being happy and living without conflict is a universal guarantee of the mental health of every individual - every person.

Read also...

- Tasks for children to find an extra object

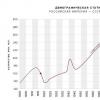

- Population of the USSR by year: population censuses and demographic processes All-Union Population Census 1939

- Speech material for automating the sound P in sound combinations -DR-, -TR- in syllables, words, sentences and verses

- The following word games Exercise the fourth extra goal