“About two great sinners” (Analysis of the legend from N. Nekrasov’s poem “Who Lives Well in Rus'”). About two great sinners. Analysis of the legend from the poem by N.A. Nekrasov Who Lives Well in Rus' Kudeyar Who Lives Well in Rus' Characteristics

(Don't forget to listen to this ballad performed by Chaliapin, and only him!!!)

ABOUT TWO GREAT SINNERS

Let us pray to the Lord God,

Let's proclaim the ancient story,

He told it to me in Solovki

Monk, Father Pitirim.

There were twelve thieves

There was Kudeyar-ataman,

Many robbers prol or

The blood of honest Christians,

They stole a lot of wealth

We lived in a dense forest,

Leader Kudeyar from near Kyiv

He took out a beautiful girl.

I amused myself with my lover during the day,

At night he made raids,

Suddenly the fierce robber

God awakened my conscience.

The dream flew away; disgusted

Drunkenness, murder, robbery,

The shadows of the slain are

A whole army - you can't count it!

I fought and resisted for a long time

Lord the beast is man.

Blown off his lover's head

And he spotted Esaul.

The villain's conscience overcame him,

He disbanded his gang,

He distributed property to the church,

I buried the knife under the willow tree.

And atone for sins

He goes to the Holy Sepulchre,

Wanders, prays, repents,

It doesn't get any easier for him.

An old man, in monastic clothes,

The sinner has returned home

Lived under the canopy of the oldest

Oak, in a forest slum.

Day and night of the Almighty

He prays: forgive your sins!

Submit your body to torture.

Just let me save my soul!

God took pity on salvation

The schema-monk showed the way:

Elder in prayer vigil

A certain saint appeared

Rek: “Not without divine providence

You chose a centuries-old oak tree,

With the same knife that he robbed,

Cut it off with the same hand!

There will be great work

There will be a reward for labor;

The tree has just fallen -

The chains of sin will fall."

The hermit measured the monster:

Oak - three girths all around!

I went to work with prayer,

Cuts with a damask knife.

Cuts resilient wood

Sings glory to the Lord,

As the years go by, it gets better

Slowly things move forward.

What can one do with a giant?

A frail, sick person?

We need iron forces here,

We don't need senility!

Doubt creeps into the heart,

Cuts and hears the words:

"Hey old man, what are you doing?"

Crossed himself first.

I looked and Pan Glukhovsky

He sees on a greyhound horse,

Sir rich, noble,

The first one in that direction.

A lot of cruel, scary

The old man heard about the master

And as a lesson to the sinner

He told his secret.

Pan grinned: “Salvation

I haven't had tea for a long time,

In the world I honor only a woman,

Gold, honor and wine.

You have to live, old man, in my opinion:

How many slaves do I destroy?

I torment, torture and hang,

I wish I could see how I’m sleeping!”

A miracle happened to the hermit:

I felt furious anger

He rushed to Pan Glukhovsky,

The knife stuck into his heart!

Just now pan bloody

I fell my head on the saddle,

A huge tree collapsed,

The echo shook the whole forest.

The tree collapsed and rolled down

The monk is off the burden of sins!..

Let us pray to the Lord God:

Have mercy on us, dark slaves!

/Option:

The tree collapsed and rolled down

The monk is off the burden of sins!..

Glory to the omnipresent creator

Today and forever and ever!

Nekrasov "Who Lives Well in Rus'"

Many people write that this is a folk song - and indeed, there are several options. But precisely this ballad by Nekrasov. Personally, I heard it performed by Chaliapin on a record while still at school - and since then any other performance seems insufficient to me, to put it mildly.

The tale of Kudeyar-Ataman is contained in the chapter “A Feast for the Whole World” of the poem “Who Lives Well in Rus'.” Nekrasov died on January 8 (new style) 1878, leaving the poem unfinished. The author did not know what the ending should be, and could not find an answer to the question of who should live well in Rus'.

The prototype of Pan Glukhovsky could be the real Smolensk landowner of the mid-19th century, Glukhovsky, who pinned a peasant to death, as reported by Herzen’s “Bell” dated October 1, 1859.

The seriously ill Nekrasov tried to publish the chapter “A Feast for the Whole World” in Otechestvennye zapiski for November 1876, and then for January 1877, but both times he was refused by the censor. The chapter was published posthumously in the illegal edition of the St. Petersburg Free Printing House in 1879. In 1881, a distorted and truncated version was published in the February issue of Otechestvennye zapiski.

The release of the chapter coincided with the peak of the Narodnaya Volya terror, which culminated in March 1881 with the murder of Alexander II.

KUDEYAR'S GOLD

On one fine April day in 1881 in St. Petersburg, on Liteiny Prospekt, a bell rang above the door of a jewelry store.

The plump owner of the shop, with a gray goatee, came out to meet the visitor.

In the doorway stood a black-mustachioed, stocky man, clearly a provincial, with a small package in his hands.

- What do you want? - asked the jeweler.

“I heard that you are buying antique jewelry,” the newcomer said uncertainly.

- Do you want to offer me something?

- Yes... Here, if you please, take a look.

The visitor placed the package on the counter and unwrapped it. The jeweler gasped. On the counter lay a massive hammered gold ladle of ancient work, decorated with semi-precious stones, and several gold and silver rings with enamel, rubies and turquoise.

“These are very ancient things,” the jeweler said half-questioningly, half-affirmatively, looking at the visitor over the glasses of his pince-nez.

Yes. These are things from a treasure that was found on my land. I am a landowner, from the Kursk province, I have a small dacha there, more than two hundred dessiatines. They say this is Kudeyar's gold...

Gold of Kudeyar... Truly, of all the legends about “enchanted treasures”, this is the biggest mystery that has not yet been resolved. Everything is unclear here. Who is Kudeyar? When and where did he live? How many treasures did he have and where are they?

Where and how did he end his life of robbery? There is not a single reliable evidence, not a single reliable document, nothing.

Only legends and numerous Kudeyarov “small towns” scattered from the Dnieper to the Volga, ravines, mounds, stones, forests, tracts... And treasures.

Treasures full of countless treasures that are still hidden somewhere throughout the entire space of the former Wild Field...

Kudeyar remembered that he was a Christian and made a vow to atone for serious sins. He let all his fellows go and was left alone. He closed all the passages into his underground dwelling and began to live alone under the mountain, atone for his own and other people’s sins before the Lord.

It is believed that Kudeyar is still alive and guards his treasures in Kudeyar Mountain in a dugout. During the day this dugout is invisible, but at night a huge bird flies in and pecks Kudeyar’s head to the brain, flying away towards dawn. He has been doomed for two centuries to guard his treasures in the mountain and bears God's punishment for robbery. In the dugout lies a loaf of bread that never diminishes.

According to other sources, Kudeyar pledged all his treasures for 200 years. This deadline has already passed. Workers must dig in odd numbers. The golden key to the iron doors lies in Sim's spring, and only the one who drains this spring or draws water from Lake Supper can get it. No one knows where it is, Dinner Lake..

The robber Kudeyar is one of the most popular characters in folklore. Legends about him are recorded in all southern and central provinces of Russia - from Smolensk to Saratov:

“And then there was Kudeyar - this one didn’t rob anywhere! And in Kaluga, and in Tula, and to Ryazan, and to Yelets, and to Voronezh, and to Smolensk - he visited everywhere, set up his camps everywhere and buried many treasures in the ground, but all with curses: he was a terrible sorcerer. And what filthy power he wielded: he would spread out his fur coat or retinue on the banks of a river, lake, or whatever stream, and go to bed; sleeps with one eye, watches with the other: is there a chase somewhere; the right eye has fallen asleep - the left one is watching, and there - the left is sleeping, the right is watching - so in alternation; and when he sees the detectives somewhere, he jumps to his feet, throws the sheepskin coat he was sleeping on into the water, and that sheepskin coat becomes not a sheepskin coat, but a boat with oars; Kudeyar will get into that boat - remember his name...

So he died his own death - they couldn’t catch him, no matter how hard they tried.”

This is just one of the short biographies of Kudeyar that existed among the people. What real historical character is hidden behind this name? Many hypotheses have already been expressed on this score, but, alas, none of them sheds light on the mystery of Kudeyar.

When did Kudeyar live? Here the opinions are basically the same: in the middle of the 16th century. He was a contemporary of Ivan the Terrible. This is partly confirmed by documents. So, in 1640, in response to a request from Moscow, the Tula governor wrote that “old people told him about Kudeyar a long time ago, about forty years ago.”

WHAT DO THE LEGENDS SAY ABOUT...

Most historians also agree that the name Kudeyar (Khudoyar) is of Tatar origin.

Karamzin mentions the Crimean Murza Kudoyar, who in 1509 treated the Russian ambassador Morozov very rudely, calling him a “servant.” The Crimean and Astrakhan ambassadors are known with the same name. But, as often happened in the past, this name could have been adopted from the Tatars by the Russians.

Many legends directly call Kudeyar a Tatar. According to legends recorded in the Saratov and Voronezh provinces, Kudeyar was a Tatar who knew Russian and a man of enormous stature.

He was a baskak - the khan's tax collector. Having plundered the villages near Moscow and returning with great wealth to the Horde, to the Saratov steppes, Kudeyar decided on the way to hide the tribute he had taken from the khan and settled in the Voronezh lands, where he began to engage in robbery. Here he married a Russian girl - a rare beauty, whom he took away by force.

In Ryazan and some areas of the Voronezh province they said that Kudeyar was a disgraced guardsman who stole livestock from local residents, robbed and killed Moscow merchants. And in the Sevsky district of the Oryol province, Kudeyar was generally considered not a person, but an unclean spirit - a “storekeeper” who guards enchanted treasures.

Historical documents dating back to the time of Ivan the Terrible mention the son of a boyar from the city of Belev, Kudeyar Tishenkov, a traitor who defected to the Crimean Khan and helped him take control of Moscow in 1571.

Then Kudeyar Tishenkov left with the Tatars for Crimea. Talking with the Crimean ambassador two years later, Ivan the Terrible complained that the khan managed to take Moscow with the help of the traitor boyars and the “robber Kudeyar Tishenkov,” who led the Tatars to Moscow. However, nothing indicates that Kudeyar Tishenkov is the legendary robber Kudeyar.

A very popular fascinating hypothesis is that Kudeyar is none other than the elder brother of Ivan the Terrible, a contender for the Russian throne. The basis for such statements was the following historical events.

The first wife of Grand Duke Vasily Ivanovich, father of Ivan the Terrible, Solomonia Saburova was childless. After much waiting, it became clear that the prince would have no heirs. Then Solomonia Saburova, in violation of all church canons, was forcibly tonsured into a monastery, and the prince remarried Elena Glinskaya, who bore him two sons - Ivan and George (Yuri).

Meanwhile, the nun Solomonia Saburova, imprisoned in a monastery... also had a son! The newborn soon died and was buried in the Suzdal Intercession Monastery. However, excavations of his grave in 1934 showed that a doll dressed as a boy was buried. There is an assumption that the child was hidden, fearing assassins sent by his second wife, Elena Glinskaya, and secretly transported to the Crimean Khan. There he grew up, and under the Tatar name Kudeyar came to Rus' as a contender for the throne. Having failed to achieve success, Kudeyar took up robbery.

As you can see, almost all of the above hypotheses connect Kudeyar with the Crimean Khanate. And the places where, according to legend, Kudeyar robbed, despite their geographical dispersion, are united by one common feature: ancient trade and embassy routes from Crimea to Muscovite Rus' passed here. On these roads, robbers tracked down rich booty, and then hid it in secret places near their camps and settlements.

About a hundred Kudeyarov towns, where, according to legend, the robbers' treasures are buried, are known in Southern Russia. There were especially many such towns within the Voronezh province. Thus, in the Thorn Forest near the village of Livenki in Pavlovsky district, there were the remains of Kudeyar’s “lair,” which included a house, storerooms and stables. Many legends about the robberies of the terrible chieftain are associated with this place.

A secluded place called Kudeyarov Log was pointed out in the Zadonsk district - it is located six miles from the village of Belokolodskoye, on the road to Lipetsk. This deep ravine is surrounded by steep, almost vertical slopes, which made it a safe refuge.

An embankment settlement, clearly made by human hands, called Kudeyarov Priton, was known in Bobrovsky district. The settlement is in the form of a large quadrangle, surrounded by ramparts and a ditch, surrounded on all sides by swamps and bushes. Here, as legends say, Kudeyar’s first headquarters was located.

In the Lipetsk region, on the Don, opposite the village of Dolgoye, there rises a mountain called Cherny Yar, or Gorodok. On it lies a very large stone of a bluish color. According to legend, the Kudeyarov fortress was located here. The stone lying on the mountain was considered to be Kudeyar’s enchanted, petrified horse, which received a bluish color because it was scorched by fire. They say that Kudeyar, together with his comrades Boldyr and the robber Anna, hiding in the Don forests, robbed the caravans of merchants going down the Don. The Don Cossacks, interested in the safety of the route, took up arms against Kudeyar. First they defeated the stakes of Boldyr and Anna, then they reached Kudeyar’s refuge.

They besieged the Kudeyar fortress for a long time, then they decided to cover it with brushwood and set it on fire from all sides. Then Kudeyar buried all his treasures in the ground, placed his favorite horse over them, turning it into stone so that it would not burn, and he himself fled into the forest. But the Cossacks chased him, captured him by cunning, shackled him and threw him from the Black Yar to the Don.

WHY DO WE SAY THIS? (folk St. Petersburg legend)

...and they threw the glorious ataman Kudeyar into the prison castle of Kresty, so that he could await the tsar’s reprisal and other investigative actions there. And in those Crosses the commandant-voivode, a selfish soul, only thinks about how to lay his raking paw on Kudeyarov’s hidden treasures.

While the Tsar's court and the sovereign's case were there, he began to torture the ataman

“Answer,” the enemy’s son yells, where did he bury the loot?!!!

- Isn’t hoo-hoo ho-ho? – that’s all Kudeyar said and showed with his shackled hands.

The governor became furious, pulled out a saber and in one fell swoop cut off the head of the riotous ataman.

And suddenly he hears the royal privets shouting at the Gate of the Crosses:

- The villain Kudeyar-ataman was ordered to present himself before the bright eyes of His Majesty!!!

The commandant-voivode was frightened, and nothing could be fixed, or even buried or hidden. All he had time to do was grab the chieftain’s head by the curls and throw him over the prison walls into the nearest weeds.

And the messenger is already on the doorstep:

- Well, where is your sovereign’s especially important prisoner??

- So... - the governor hesitated, - how can I tell you....

He hesitated, but did not dare to lie to the Tsar’s envoy:

- The chest is in the Crosses, and the head is in the bushes. (Dubious and funny version)

Not far away, in the former Pronsky district, near the villages of Chulkovo and Abakumovo, there is the Kamennye Kresttsy tract. According to legend, one of Kudeyar’s main headquarters was located here. They say that in the 18th century a stone with the name Kudeyar was found here.

On the Neruch River in the Oryol province, three versts from the village of Zatishye, there are two “Kudeyar pits” - three fathoms deep, connected by an underground passage to the Neruch River. Here, as they say, Kudeyar was hiding. Many of Kudeyar’s treasures are associated with the Bryansk forests and, in general, with the entire forested part of the former Oryol province.

http://new-burassity.3dn.ru/publ/1-1-0-3

KUDEYAROVO GORODISHE

In the Tula and Kaluga provinces, legends tell of Kudeyar’s treasures buried in various “wells”, “tops”, “yars”, and in some places “treasury records” of Kudeyar’s treasures were preserved.

At the end of the last century, one of these records was owned by a monk of Optina Pustyn, after whose death the manuscript ended up in the monastery library. It contained extensive information about the treasures buried by Kudeyar in the vicinity of Kozelsk and Likhvin (now Chekalin).

As one of the places where Kudeyar's treasures were hidden, the manuscript named Devil's Settlement, or Shutova Gora, which is 18 miles from the Optina Pustyn monastery, not far from the ancient road from Kozelsk to Likhvin, on which it was so convenient to rob passing merchants.

On a high hill overgrown with forest, dominating the surrounding area, almost at its very top, a huge block of grayish sandstone, furrowed with cracks and overgrown with moss, rises from the ground with three sheer walls. Because of these clear edges, Devil's Settlement was sometimes also called Granny Hill. The fourth side of the Settlement, dilapidated by time and overgrown with grass, is almost level with the platform at the top of the hillock, forming a “courtyard”.

According to legend, Kudeyar’s “castle” was located here, built for him by evil spirits. As if in one night the demons built a two-story stone house, a gate, and dug a pond on the site of the Settlement... However, they did not have time to finish the construction before dawn - the rooster crowed, and the evil spirits fled. And, according to witnesses, a long time later, right up to early XIX century, on the Settlement one could see an unfinished building - a “monument of demonic architecture”, which then began to quickly collapse.

Traces of the pond dug by the “demons” were noticeable back in the 80s of the last century; Numerous stone fragments scattered around the Settlement seemed to indicate some kind of buildings that had once been here.

And on one of the stones that lay at the foot of the Settlement, a hundred years ago the trace of the “paw” of the unclean was clearly visible. Several caves are hidden in the thickness of the sandstone from which the Settlement is made. The main cave, called the “entrance to the lower floor,” could comfortably accommodate several people. From it two narrow holes go deep into the mountain...

They say that the evil spirits that built the castle are now preserving Kudeyar’s treasures buried on Gorodishche, in the surrounding ravines and forest tracts. But at night the ghost of Kudeyar’s daughter Lyubusha appears on the Settlement, cursed by her father and forever imprisoned in the depths of the Devil’s Settlement. It’s as if she goes out onto the mountain, sits on the stones and cries, asking: “It’s hard for me! Give me the cross! In former times, the monks of Optina Pustyn erected a cross on the Settlement twice. Not far from the Settlement is the Kudeyarov well, in which, according to legend, “12 barrels of gold” are hidden.

Very interesting are the testimonies about the Kudeyarov Town on Mount Bogatyrka (Krutse), in the Saratov province. Here, in the ruins of a dugout, in which, according to legend, , Kudeyar lived, human bones, daggers, pike tips, reeds, fragments of chain mail, Tatar coins, rings, rings, etc. were found. Such finds invariably aroused interest in the legendary treasures of Kudeyar, and there were a great many hunters to find them...

Kudeyarovo Settlement, located in the wilds of the Usman Forest, was of particular interest to treasure hunters. It is surrounded by a high rampart with traces of a gate and surrounded by a wide ditch. Once upon a time, in the 40s of the last century, one of the peasant women of the village of Studenki was lucky enough to find a massive gold antique ring here.

Since then, every spring, hordes of treasure hunters from all surrounding places regularly rushed into the Usman forest, dug up the forest with holes and trenches. They said that the treasures were hidden at the bottom of the nearby Clear Lake. One landowner even tried to drain the lake through a specially dug canal, but it didn’t work out. There was a lot of talk about a chest allegedly found in the forest that “went into the ground,” and all sorts of little things were found, but Kudeyar’s main treasures have not yet been discovered.

But in other places, treasure hunters had better luck. It cannot be said that treasure finds were widespread, but at least four cases are known when treasures of silver coins and a few gold objects were found precisely in the Kudeyarov tracts.

Did these treasures belong to the legendary robber? Unknown. And in general, it’s hard to believe that one person could “populate” vast expanses of the steppe. The opinion has long been expressed that several different people could be hiding under the name Kudeyar - like under the names of Tsarevich Dmitry or Peter III. Or maybe, from the personal name of some particularly daring Russian or Tatar robber, the name Kudeyar turned into a common noun for every leader of a bandit gang and became synonymous with the word “robber”?

That is why the versions about the origin, life and death of Kudeyar vary so much. That’s why we have so many kudeyars - for whatever reason, but from time immemorial there has been no shortage of robbers in Rus'. And already at the end of the 18th century, legends began to take shape about how “in the old, old years, seven Kudeyar brothers lived in Spassky places...”

http://www.vokrugsveta.com/S4/proshloe/kudiyar.htm

About two great sinners

Let us pray to the Lord God,

Let's proclaim the ancient story,

He told it to me in Solovki

Monk, Father Pitirim.

There were twelve thieves

There was Kudeyar - ataman,

The robbers shed a lot

The blood of honest Christians,

They stole a lot of wealth

We lived in a dense forest,

Leader Kudeyar from near Kyiv

He took out a beautiful girl.

I amused myself with my lover during the day,

At night he made raids,

Suddenly the fierce robber

God awakened my conscience.

The dream flew away; disgusted

Drunkenness, murder, robbery,

The shadows of the slain are

A whole army - you can't count it!

I fought and resisted for a long time

Lord beast-man,

Blown off his lover's head

And he spotted Esaul.

The villain's conscience overcame him,

He disbanded his gang,

He distributed property to the church,

I buried the knife under the willow tree.

And atone for sins

He goes to the Holy Sepulchre,

Wanders, prays, repents,

It doesn't get any easier for him.

An old man, in monastic clothes,

The sinner has returned home

Lived under the canopy of the oldest

Oak, in a forest slum.

Day and night of the Almighty

He prays: forgive your sins!

Submit your body to torture

Just let me save my soul!

God took pity on salvation

The schema-monk showed the way:

Elder in prayer vigil

A certain saint appeared

River "Not without God's providence"

You chose an age-old oak tree,

With the same knife that he robbed,

Cut it off with the same hand!

There will be great work

There will be a reward for work;

The tree has just fallen -

The chains of sin will fall."

The hermit measured the monster:

Oak - three girths all around!

I went to work with prayer,

Cuts with a damask knife,

Cuts resilient wood

Sings glory to the Lord,

As the years go by, it gets better

Slowly things move forward.

What can one do with a giant?

A frail, sick person?

We need iron forces here,

We don't need senility!

Doubt creeps into the heart,

Cuts and hears the words:

"Hey old man, what are you doing?"

Crossed himself first

I looked and Pan Glukhovsky

He sees on a greyhound horse,

Sir rich, noble,

The first one in that direction.

A lot of cruel, scary

The old man heard about the master

And as a lesson to the sinner

He told his secret.

Pan grinned: “Salvation

I haven't had tea for a long time,

In the world I honor only a woman,

Gold, honor and wine.

You have to live, old man, in my opinion:

How many slaves do I destroy?

I torment, torture and hang,

I wish I could see how I’m sleeping!”

A miracle happened to the hermit:

I felt furious anger

He rushed to Pan Glukhovsky,

The knife stuck into his heart!

Just now pan bloody

I fell my head on the saddle,

A huge tree collapsed,

The echo shook the whole forest.

The tree collapsed and rolled down

The monk is off the burden of sins!..

Let us pray to the Lord God:

Have mercy on us, dark slaves!

Veretennikov Pavlusha - a collector of folklore who met men - seekers of happiness - at a rural fair in the village of Kuzminskoye. This character is given a very meager external characteristic(“He was good at acting out, / Wore a red shirt, / A cloth undergirl, / Grease boots...”), little is known about his origin (“What kind of rank, / The men did not know, / However, they called him “master”) . Due to such uncertainty, V.’s image acquires a generalizing character. His keen interest in the fate of the peasants distinguishes V. from among indifferent observers of the life of the people (figures of various statistical committees), eloquently exposed in the monologue of Yakim Nagogo. V.’s first appearance in the text is accompanied by a selfless act: he helps out the peasant Vavila by buying shoes for his granddaughter. In addition, he is ready to listen to other people's opinions. So, although he condemns the Russian people for drunkenness, he is convinced of the inevitability of this evil: after listening to Yakim, he himself offers him a drink (“Veretennikov / He brought two scales to Yakim”). Seeing the genuine attention from the reasonable master, and “the peasants open up / to the gentleman’s liking.” Among the alleged prototypes of V. are folklorists and ethnographers Pavel Yakushkin and Pavel Rybnikov, figures of the democratic movement of the 1860s. The character probably owes his surname to the journalist P.F. Veretennikov, who visited the Nizhny Novgorod Fair for several years in a row and published reports about it in the Moskovskie Vedomosti.

Vlas- headman of the village of Bolshie Vakhlaki. “Serving under a strict master, / Bearing the burden on his conscience / An involuntary participant / in his cruelties.” After the abolition of serfdom, V. renounced the post of pseudo-burgomaster, but accepted actual responsibility for the fate of the community: “Vlas was the kindest soul, / He was rooting for the entire Vakhlachin - / Not for one family.” When the hope for the Last One flashed with the death free life “without corvee... without taxes... Without a stick...” is replaced for the peasants by a new concern (litigation with the heirs for the flood meadows), V. becomes an intercessor for the peasants, “lives in Moscow... was in St. Petersburg ... / But there’s no point!” Along with his youth, V. gave up his optimism, is afraid of new things, and is always gloomy. But his daily life is rich in unnoticeable good deeds, for example, in the chapter “A Feast for the Whole World.” on his initiative, the peasants collect money for the soldier Ovsyanikov. The image of V. is devoid of external concreteness: for Nekrasov, he is, first of all, a representative of the peasantry. ) - the fate of the entire Russian people.

Girin Ermil Ilyich (Ermila) - one of the most likely candidates for the title of lucky. The real prototype of this character is the peasant A.D. Potanin (1797-1853), who managed by proxy the estate of Countess Orlova, which was called Odoevshchina (after the surnames of the former owners - the Odoevsky princes), and the peasants were baptized into Adovshchina. Potanin became famous for his extraordinary justice. Nekrasovsky G. became known to his fellow villagers for his honesty even in the five years that he served as a clerk in the office (“You need a bad conscience - / A peasant should extort a penny from a peasant”). Under the old Prince Yurlov, he was fired, but then, under the young Prince, he was unanimously elected mayor of Adovshchina. During the seven years of his “reign” G. only once betrayed his soul: “... from the recruiting / He shielded his younger brother Mitri.” But repentance for this offense almost led him to suicide. Only thanks to the intervention of a strong master was it possible to restore justice, and instead of Nenila Vlasyevna’s son, Mitriy went to serve, and “the prince himself takes care of him.” G. quit his job, rented the mill “and it became more powerful than ever / Loved by all the people.” When they decided to sell the mill, G. won the auction, but he did not have the money with him to make a deposit. And then “a miracle happened”: G. was rescued by the peasants to whom he turned for help, and in half an hour he managed to collect a thousand rubles in the market square.

G. is driven not by mercantile interest, but by a rebellious spirit: “The mill is not dear to me, / The resentment is great.” And although “he had everything he needed / For happiness: peace, / And money, and honor,” at the moment when the peasants start talking about him (chapter “Happy”), G., in connection with the peasant uprising, is in prison. The speech of the narrator, a gray-haired priest, from whom it becomes known about the arrest of the hero, is unexpectedly interrupted by outside interference, and later he himself refuses to continue the story. But behind this omission one can easily guess both the reason for the riot and G.’s refusal to help in pacifying it.

Gleb- peasant, “great sinner.” According to the legend told in the chapter “A Feast for the Whole World”, the “ammiral-widower”, participant in the battle “at Achakov” (possibly Count A.V. Orlov-Chesmensky), granted by the empress with eight thousand souls, dying, entrusted to the elder G. his will (free for these peasants). The hero was tempted by the money promised to him and burned the will. Men tend to regard this “Judas” sin as the most serious sin ever committed, and because of it they will have to “suffer forever.” Only Grisha Dobrosklonov manages to convince the peasants “that they are not responsible / For Gleb the accursed, / It’s all their fault: strengthen yourself!”

Dobrosklonov Grisha - a character who appears in the chapter “A Feast for the Whole World”; the epilogue of the poem is entirely dedicated to him. “Gregory / Has a thin, pale face / And thin, curly hair / With a tinge of redness.” He is a seminarian, the son of the parish sexton Trifon from the village of Bolshiye Vakhlaki. Their family lives in extreme poverty, only the generosity of Vlas the godfather and other men helped put Grisha and his brother Savva on their feet. Their mother Domna, “an unrequited farmhand / For everyone who helped her in any way / on a rainy day,” died early, leaving a terrible “Salty” song as a reminder of herself. In D.’s mind, her image is inseparable from the image of her homeland: “In the boy’s heart / With love for his poor mother / Love for all the Vakhlachina / Merged.” Already at the age of fifteen he was determined to devote his life to the people. “I don’t need silver, / Nor gold, but God grant, / So that my fellow countrymen / And every peasant / May live freely and cheerfully / Throughout all holy Rus'!” He is going to Moscow to study, while in the meantime he and his brother help the peasants as best they can: they write letters for them, explain the “Regulations on peasants emerging from serfdom,” work and rest “on an equal basis with the peasantry.” Observations on the life of the surrounding poor, reflections on the fate of Russia and its people are clothed in poetic form, D.'s songs are known and loved by the peasants. With his appearance in the poem, the lyrical principle intensifies, the author’s direct assessment invades the narrative. D. is marked with the “seal of the gift of God”; a revolutionary propagandist from among the people, he should, according to Nekrasov, serve as an example for the progressive intelligentsia. Into his mouth the author puts his beliefs, his own version of the answer to the social and moral questions posed in the poem. The image of the hero gives the poem compositional completeness. Real prototype could be N.A. Dobrolyubov.

Elena Alexandrovna - governor's wife, merciful lady, Matryona's savior. “She was kind, she was smart, / Beautiful, healthy, / But God did not give children.” She sheltered a peasant woman after a premature birth, became the child’s godmother, “all the time with Liodorushka / Was worn around like her own.” Thanks to her intercession, it was possible to rescue Philip from the recruiting camp. Matryona praises her benefactor to the skies, and criticism (O. F. Miller) rightly notes in the image of the governor echoes of the sentimentalism of the Karamzin period.

Ipat- a grotesque image of a faithful serf, a lord's lackey, who remained faithful to the owner even after the abolition of serfdom. I. boasts that the landowner “harnessed him with his own hand / to a cart,” bathed him in an ice hole, saved him from the cold death to which he himself had previously doomed. He perceives all this as great blessings. I. causes healthy laughter among wanderers.

Korchagina Matryona Timofeevna - a peasant woman, the third part of the poem is entirely devoted to her life story. “Matryona Timofeevna / A dignified woman, / Broad and dense, / About thirty-eight years old. / Beautiful; gray hair, / Large, stern eyes, / Rich eyelashes, / Severe and dark. / She’s wearing a white shirt, / And a short sundress, / And a sickle over her shoulder.” The fame of the lucky woman brings strangers to her. M. agrees to “lay out her soul” when the men promise to help her in the harvest: the suffering is in full swing. M.'s fate was largely suggested to Nekrasov by the autobiography of the Olonets screamer I. A. Fedoseeva, published in the 1st volume of “Lamentations of the Northern Territory” collected by E. V. Barsov (1872). The narrative is based on her laments, as well as other folklore materials, including “Songs collected by P. N. Rybnikov” (1861). The abundance of folklore sources, often included practically unchanged in the text of “The Peasant Woman,” and the very title of this part of the poem emphasize the typicality of M.’s fate: this is the usual fate of a Russian woman, convincingly indicating that the wanderers “started / Not a matter between women / / Look for a happy one.” In his parents' house, in a good, non-drinking family, M. lived happily. But, having married Philip Korchagin, a stove maker, she ended up “by her maiden will in hell”: a superstitious mother-in-law, a drunken father-in-law, an older sister-in-law, for whom the daughter-in-law must work like a slave. However, she was lucky with her husband: only once did it come to beatings. But Philip only returns home from work in the winter, and the rest of the time there is no one to intercede for M. except grandfather Savely, father-in-law. She has to endure the harassment of Sitnikov, the master's manager, which stopped only with his death. For the peasant woman, her first-born De-mushka becomes a consolation in all troubles, but due to Savely’s oversight, the child dies: he is eaten by pigs. An unjust trial is being carried out on a grief-stricken mother. Having not thought of giving a bribe to her boss in time, she witnesses the violation of her child’s body.

For a long time, K. cannot forgive Savely for his irreparable mistake. Over time, the peasant woman has new children, “there is no time / Neither to think nor to grieve.” The heroine's parents, Savely, die. Her eight-year-old son Fedot faces punishment for feeding someone else's sheep to a wolf, and his mother lies under the rod in his place. But the most difficult trials befall her in a lean year. Pregnant, with children, she herself is like a hungry wolf. The recruitment deprives her of her last protector, her husband (he is taken out of turn). In her delirium, she draws terrible pictures of the life of a soldier and soldiers’ children. She leaves the house and runs to the city, where she tries to get to the governor, and when the doorman lets her into the house for a bribe, she throws herself at the feet of the governor Elena Alexandrovna. With her husband and newborn Liodorushka, the heroine returns home, this incident secured her reputation as a lucky woman and the nickname “governor”. Her further fate is also full of troubles: one of her sons has already been taken into the army, “They were burned twice... God visited with anthrax... three times.” The “Woman’s Parable” sums up her tragic story: “The keys to women’s happiness, / From our free will / Abandoned, lost / From God himself!” Some of the critics (V.G. Avseenko, V.P. Burenin, N.F. Pavlov) met “The Peasant Woman” with hostility; Nekrasov was accused of implausible exaggerations, false, fake populism. However, even ill-wishers noted some successful episodes. There were also reviews of this chapter as the best part of the poem.

Kudeyar-ataman - “great sinner”, the hero of the legend told by God’s wanderer Jonushka in the chapter “A Feast for the Whole World”. The fierce robber unexpectedly repented of his crimes. Neither a pilgrimage to the Holy Sepulcher nor a hermitage brings peace to his soul. The saint who appeared to K. promises him that he will earn forgiveness when he cuts down a century-old oak tree “with the same knife that he robbed.” Years of futile efforts raised doubts in the heart of the old man about the possibility of completing the task. However, “the tree collapsed, the burden of sins rolled off the monk,” when the hermit, in a fit of furious anger, killed Pan Glukhovsky, who was passing by, boasting of his calm conscience: “Salvation / I haven’t been drinking for a long time, / In the world I honor only woman, / Gold, honor and wine... How many slaves I destroy, / I torture, torture and hang, / And if only I could see how I’m sleeping!” The legend about K. was borrowed by Nekrasov from folklore tradition, but the image of Pan Glukhovsky is quite realistic. Among the possible prototypes is the landowner Glukhovsky from the Smolensk province, who spotted his serf, according to a note in Herzen’s “Bell” dated October 1, 1859.

Nagoy Yakim- “In the village of Bosovo / Yakim Nagoy lives, / He works until he’s dead, / He drinks until he’s half to death!” - this is how the character defines himself. In the poem, he is entrusted to speak out in defense of the people on behalf of the people. The image has deep folklore roots: the hero’s speech is replete with paraphrased proverbs, riddles, in addition, formulas similar to those that characterize his appearance (“The hand is tree bark, / And the hair is sand”) are repeatedly found, for example, in folk spiritual verse "About Yegoriy Khorobry." Nekrasov reinterprets the popular idea of the inseparability of man and nature, emphasizing the unity of the worker with the earth: “He lives and tinkers with the plow, / And death will come to Yakimushka” - / As a lump of earth falls off, / What has dried on the plow ... near the eyes, near the mouth / Bends like cracks / On dry ground<...>the neck is brown, / Like a layer cut off by a plow, / A brick face.”

The character’s biography is not entirely typical for a peasant, it is rich in events: “Yakim, a wretched old man, / Once lived in St. Petersburg, / But he ended up in prison: / He decided to compete with a merchant! / Like a piece of velcro, / He returned to his homeland / And took up the plow.” During the fire, he lost most of his property, since the first thing he did was rush to save the pictures that he bought for his son (“And he himself, no less than the boy / Loved to look at them”). However, even in the new house, the hero returns to the old ways and buys new pictures. Countless adversities only strengthen his firm position in life. In Chapter III of the first part (“Drunken Night”) N. pronounces a monologue, where his beliefs are formulated extremely clearly: hard labor, the results of which go to three shareholders (God, the Tsar and the Master), and sometimes are completely destroyed by fire; disasters, poverty - all this justifies peasant drunkenness, and it is not worth measuring the peasant “by the master’s standard.” This point of view on the problem of popular drunkenness, widely discussed in journalism in the 1860s, is close to the revolutionary democratic one (according to N. G. Chernyshevsky and N. A. Dobrolyubov, drunkenness is a consequence of poverty). It is no coincidence that this monologue was subsequently used by the populists in their propaganda activities, and was repeatedly rewritten and reprinted separately from the rest of the text of the poem.

Obolt-Obolduev Gavrila Afanasyevich - “The gentleman is round, / Mustachioed, pot-bellied, / With a cigar in his mouth... ruddy, / Stately, stocky, / Sixty years old... Well done, / Hungarian with Brandenburs, / Wide trousers.” Among O.'s eminent ancestors are a Tatar who amused the empress with wild animals, and an embezzler who plotted the arson of Moscow. The hero is proud of his family tree. Previously, the master “smoked... God’s heaven, / Wore the royal livery, / Wasted the people’s treasury / And thought to live like this forever,” but with the abolition of serfdom, “the great chain broke, / It broke and sprang apart: / One end hit the master, / For others, it’s a man!” With nostalgia, the landowner recalls the lost benefits, explaining along the way that he is sad not for himself, but for his motherland.

A hypocritical, idle, ignorant despot, who sees the purpose of his class in “the ancient name, / The dignity of the nobility / To support with hunting, / With feasts, with all kinds of luxury / And to live by the labor of others.” On top of that, O. is also a coward: he mistakes unarmed men for robbers, and they do not soon manage to persuade him to hide the pistol. The comic effect is enhanced by the fact that accusations against oneself come from the lips of the landowner himself.

Ovsyanikov- soldier. “...He was fragile on his legs, / Tall and skinny to the extreme; / He was wearing a frock coat with medals / Hanging like on a pole. / It’s impossible to say that he had a kind / face, especially / When he drove the old one - / Damn the devil! The mouth will snarl, / The eyes are like coals!” With his orphan niece Ustinyushka, O. traveled around the villages, earning a living from the district committee, when the instrument became damaged, he composed new sayings and performed them, playing along with himself on spoons. O.'s songs are based on folklore sayings and raesh poems recorded by Nekrasov in 1843-1848. while working on “The Life and Adventures of Tikhon Trostnikovaya. The lyrics of these songs sketch out life path soldier: the war near Sevastopol, where he was crippled, a negligent medical examination, where the old man’s wounds were rejected: “Second-rate! / According to them, the pension”, subsequent poverty (“Come on, with George - around the world, around the world”). In connection with the image of O., a topic that is relevant both for Nekrasov and for later Russian literature arises railway. The cast iron in the soldier’s perception is an animated monster: “It snorts in the peasant’s face, / Crushes, maims, tumbles, / Soon the entire Russian people / Will sweep cleaner than a broom!” Klim Lavin explains that the soldier cannot get to the St. Petersburg “Committee for the Wounded” for justice: the tariff on the Moscow-Petersburg road has increased and made it inaccessible to the people. The peasants, the heroes of the chapter “A Feast for the Whole World,” are trying to help the soldier and together collect only “rubles.”

Petrov Agap- “rude, unyielding,” according to Vlas, a man. P. did not want to put up with voluntary slavery; they calmed him down only with the help of wine. Caught by the Last One at the scene of the crime (carrying a log from the master’s forest), he broke down and explained his real situation to the master in the most impartial terms. Klim Lavin staged a brutal reprisal against P., getting him drunk instead of flogging him. But from the humiliation suffered and excessive intoxication, the hero dies by the morning of the next day. Such a terrible price is paid by peasants for a voluntary, albeit temporary, renunciation of freedom.

Polivanov- “... a gentleman of low birth,” however, small means did not in the least prevent the manifestation of his despotic nature. He is characterized by the whole range of vices of a typical serf owner: greed, stinginess, cruelty (“with relatives, not only with peasants”), voluptuousness. By old age, the master’s legs were paralyzed: “The eyes are clear, / The cheeks are red, / The plump arms are as white as sugar, / And there are shackles on the legs!” In this trouble, Yakov became his only support, “friend and brother,” but the master repaid him with black ingratitude for his faithful service. The terrible revenge of the slave, the night that P. had to spend in the ravine, “driving away the groans of birds and wolves,” force the master to repent (“I am a sinner, a sinner! Execute me!”), but the narrator believes that he will not be forgiven: “You will You, master, are an exemplary slave, / Faithful Jacob, / Remember until the day of judgment!

Pop- according to Luke’s assumption, the priest “lives cheerfully, / At ease in Rus'.” The village priest, who was the first to meet the wanderers on the way, refutes this assumption: he has no peace, no wealth, no happiness. With what difficulty “the priest’s son gets a letter,” Nekrasov himself wrote in the poetic play “Rejected” (1859). In the poem, this theme will appear again in connection with the image of seminarian Grisha Dobrosklonov. The priest’s career is restless: “The sick, the dying, / Born into the world / They do not choose time,” no habit will protect from compassion for the dying and orphans, “every time it gets wet, / The soul gets sick.” Pop enjoys dubious honor among the peasantry: folk superstitions are associated with him, he and his family are constant characters in obscene jokes and songs. The priest's wealth was previously due to the generosity of parishioners and landowners, who, with the abolition of serfdom, left their estates and scattered, “like the Jewish tribe... Across distant foreign lands / And across native Rus'.” With the transfer of the schismatics to the supervision of civil authorities in 1864, the local clergy lost another serious source of income, and it was difficult to live on “kopecks” from peasant labor.

Savely- the Holy Russian hero, “with a huge gray mane, / Tea, not cut for twenty years, / With a huge beard, / Grandfather looked like a bear.” Once in a fight with a bear, he injured his back, and in his old age it bent. S’s native village, Korezhina, is located in the wilderness, and therefore the peasants live relatively freely (“The zemstvo police / Haven’t come to us for a year”), although they endure the atrocities of the landowner. The heroism of the Russian peasant lies in patience, but there is a limit to any patience. S. ends up in Siberia for burying a hated German manager alive. Twenty years of hard labor, an unsuccessful attempt to escape, twenty years of settlement did not shake the rebellious spirit in the hero. Having returned home after the amnesty, he lives with the family of his son, Matryona’s father-in-law. Despite his venerable age (according to revision tales, his grandfather is a hundred years old), he leads an independent life: “He didn’t like families, / didn’t let them into his corner.” When they reproach him for his convict past, he cheerfully replies: “Branded, but not a slave!” Tempered by harsh trades and human cruelty, S.’s petrified heart could only be melted by Dema’s great-grandson. An accident makes the grandfather the culprit of Demushka's death. His grief is inconsolable, he goes to repentance at the Sand Monastery, tries to beg for forgiveness from the “angry mother.” Having lived one hundred and seven years, before his death he pronounces a terrible sentence on the Russian peasantry: “For men there are three roads: / Tavern, prison and penal servitude, / And for women in Rus' / Three nooses... Climb into any one.” The image of S, in addition to folklore, has social and polemical roots. O. I. Komissarov, who saved Alexander II from the assassination attempt on April 4, 1866, was a Kostroma resident, a fellow countryman of I. Susanin. Monarchists saw this parallel as proof of the thesis about the love of the Russian people for kings. To refute this point of view, Nekrasov settled the rebel S in the Kostroma province, the original patrimony of the Romanovs, and Matryona catches the similarity between him and the monument to Susanin.

Trophim (Tryphon) - “a man with shortness of breath, / Relaxed, thin / (Sharp nose, like a dead one, / Thin arms like a rake, / Long legs like knitting needles, / Not a man - a mosquito).” A former bricklayer, a born strongman. Yielding to the contractor’s provocation, he “carried one at the extreme / Fourteen pounds” to the second floor and broke himself. One of the most vivid and terrible images in the poem. In the chapter “Happy,” T. boasts of the happiness that allowed him to get from St. Petersburg to his homeland alive, unlike many other “feverish, feverish workers” who were thrown out of the carriage when they began to rave.

Utyatin (Last One) - "thin! / Like winter hares, / All white... Nose with a beak like a hawk, / Gray mustache, long / And - different eyes: / One healthy one glows, / And the left one is cloudy, cloudy, / Like a tin penny! Having “exorbitant wealth, / An important rank, a noble family,” U. does not believe in the abolition of serfdom. As a result of an argument with the governor, he becomes paralyzed. “It was not self-interest, / But arrogance cut him off.” The prince's sons are afraid that he will deprive them of their inheritance in favor of their side daughters, and they persuade the peasants to pretend to be serfs again. The peasant world allowed “the dismissed master to show off / During the remaining hours.” On the day of the arrival of wanderers - seekers of happiness - in the village of Bolshie Vakhlaki, the Last One finally dies, then the peasants arrange a “feast for the whole world.” The image of U. has a grotesque character. The absurd orders of the tyrant master will make the peasants laugh.

Shalashnikov- landowner, former owner of Korezhina, military man. Taking advantage of the distance from the provincial town, where the landowner and his regiment were stationed, the Korezhin peasants did not pay quitrent. Sh. decided to extract the quitrent by force, tore the peasants so much that “the brains were already shaking / In their little heads.” Savely remembers the landowner as an unsurpassed master: “He knew how to flog! / He tanned my skin so well that it lasts for a hundred years.” He died near Varna, his death put an end to the relative prosperity of the peasants.

Yakov- “about the exemplary slave - Yakov the faithful”, a former servant tells in the chapter “A Feast for the Whole World”. “People of the servile rank are / Sometimes mere dogs: / The more severe the punishment, / The dearer the Lord is to them.” So was Ya. until Mr. Polivanov, having coveted his nephew’s bride, sold him as a recruit. The exemplary slave took to drinking, but returned two weeks later, taking pity on the helpless master. However, his enemy was already “torturing him.” Ya takes Polivanov to visit his sister, halfway turns into the Devil's Ravine, unharnesses the horses and, contrary to the master's fears, does not kill him, but hangs himself, leaving the owner alone with his conscience for the whole night. This method of revenge (“to drag dry misfortune” - to hang oneself in the domain of the offender in order to make him suffer for the rest of his life) was indeed known, especially among the eastern peoples. Nekrasov, creating the image of Ya., turns to the story that A.F. Koni told him (who, in turn, heard it from the watchman of the volost government), and only slightly modifies it. This tragedy is another illustration of the destructiveness of serfdom. Through the mouth of Grisha Dobrosklonov, Nekrasov summarizes: “No support - no landowner, / Driving a zealous slave to the noose, / No support - no servant, / Taking revenge / on his villain by suicide.”

The poem “Who lives well in Rus'? - the pinnacle of N. A. Nekrasov’s creativity. It can be called an encyclopedia of Russian pre-reform and post-reform life. The breadth of the concept is enormous due to the depth of penetration into the psychology of the various classes of Russia at that time, the truthfulness, brightness and diversity of types.

The plot of the poem is very close to the folk tale about the search for the human share, about the search for happiness and truth, justice.

With all the variety of types depicted in the poem, its main character is the people, the peasantry. Truthfully depicting the difficult situation, thoughts and aspirations of the masses, Nekrasov sought a solution to the most important issues of his time: who is to blame for the people’s grief and what to do to make the people free and happy.

Many pages of the poem depict the joyless, powerless, hungry life of the people. A peasant’s happiness, according to Nekrasov’s definition, is “holey with patches, hunchbacked with calluses.” There are no happy peasants.

Hard, exhausting work does not save peasants from eternal poverty or the threat of starvation. Therefore, the poet treats the peasants who do not put up with their powerless and hungry existence with undisguised sympathy. Nekrasov finds justification for the brutal reprisals of peasants against landowners in the inhumanity of the existing order. Examples of fighters for the people's cause in the poem include Ermil Girin, Savely the hero, and the rebellious Agap.

The parable “About Two Great Sinners” occupies a special place in the poem.

Let us pray to the Lord God,

Let's recount the ancient story...

This is how the story about two sinners Nekrasov begins. The robber Kudeyar was an ataman. He lived in a dense forest and lived in robbery. There was more than one murder on his conscience. But “Suddenly the Lord awakened the conscience of the fierce robber.” Kudeyar abandons his previous way of life and, in order to calm his conscience, turns to the church and becomes a monk. Only his sins are so grave that his conscience finds no peace. The only thing the elder prays to God is: “Just let me save my soul.” In the name of atonement for sins, Kudeyar vows to cut down a huge oak tree with three girths using the knife with which he committed the murders. And he would have worked until the end of time, if not for his meeting with Mr. Glukhovsky:

A lot of cruel, scary

The old man heard about the master...

Kudeyar tries to tell his story as a lesson to the sinner, but the master is not going to change his way of life:

You have to live, old man, in my opinion:

How many slaves do I destroy?

I torment, torture and hang,

I wish I could see how I sleep.

Kudeyar's soul is filled with noble indignation, and he kills Pan Glukhovsky with one blow of a knife to the heart. The author gives the hero, seeking peace for his suffering soul, the right of fair retribution:

The tree collapsed and rolled down

The monk is off the burden of sins!..

Kudeyar, in righteous anger, kills the people's enemy, the cruel exploiter Glukhovsky. Thus, the author shows that the highest folk morality, illuminated by the authority of religious faith, justifies righteous anger against the oppressors and even violence against them.

The peculiarity of Russian literature is that it has always been closely connected with current problems public life. The great writers of Russia were deeply concerned about the fate of their homeland and people. Patriotism, citizenship and humanity were the main features of the poetry of Pushkin, Lermontov and Nekrasov. They all saw the meaning of their creativity in serving the people, in the struggle for their freedom and happiness. Both Pushkin and Lermontov affirmed the idea that the poet-prophet should “burn the hearts of people with his words,” “ignite a fighter for battle,” and bring people “pure teachings of love and truth.”

Nekrasov acted as the successor and continuer of these progressive traditions. His "muse of revenge and sorrow" became the protector of the oppressed. Nekrasov most fully outlined his views on the role of the poet and poetry in the poem “The Poet and the Citizen,” which is perceived as his poetic manifesto the main idea The author is established in polemics with those who are trying to cleanse poetry of socio-political themes, considering them unworthy of high art. On behalf of a citizen, he reproaches the poet for leading the reader away from the pressing issues of our time into the world of intimate feelings and experiences.

It’s a shame to sleep with your talent;

It’s even more shameful in a time of grief

The beauty of the valleys, skies and sea

And sing of sweet affection...

Despite the fact that most of his works are full of the most bleak pictures of people's grief, the main impression that Nekrasov leaves in his reader is undoubtedly invigorating. The poet does not give in to the sad reality, does not bow his neck obediently before it. He boldly enters into battle with the dark forces and is confident of victory. Nekrasov’s poems awaken that anger that carries within itself the seed of healing. However, the entire content of Nekrasov’s poetry is not exhausted by the sounds of revenge and sadness about the people’s grief.

The poem “Who Lives Well in Rus'” is based on the thought that haunted the poet in the post-reform years: the people are free, but did this bring them happiness? The poem is so multifaceted that it is easier to consider it in parts. In the second part, in the chapter “On Two Great Sinners,” Nekrasov examined a controversial philosophical question: is it possible to atone for evil with evil? The point is that the chieftain of the robbers Kudeyar shed a lot of innocent blood, but over time he began to be tormented by remorse. Then he “took off the head of his mistress and pinned down Esaul,” and then “an old man in monastic robes” returned to his native land, where he tirelessly prays to the Lord to forgive him his sins.

An angel appears, points to a huge oak tree, and tells Kudeyar that his sins will be forgiven only when he cuts down this oak tree with the same knife with which he killed people. The robber gets down to business. Pan Glukhovsky drives by and a conversation ensues. Glukhovsky, about whom there are terrible stories, after listening to Kudeyar, grins:

Rescue

I haven't had tea for a long time,

In the world I honor only a woman:

Gold, honor and wine.

You have to live, old man, in my opinion:

How many slaves do I destroy?

I torment, torture and hang,

I wish I could see how I sleep!

Kudeyar attacks Glukhovsky and plunges a knife into his heart. Immediately the oak tree falls, and the hermit “rolled away... the burden of sins”...

Nekrasov, for the second time, as in the episode with Savely, where the men rebelled, enters into an argument with the Christian principles of forgiveness. On behalf of the peasants, he justifies the act of the repentant robber, believing that in the people’s soul there lives a “hidden spark” that is about to flare up into a flame... To some extent, Grisha Dobrosklonov is the exponent of change, of latent rebellion. He cannot be called the hero of the poem, since he came from another life, from the world of the future, but it is he who announces the new life of “the all-powerful Mother Rus'” and calls to live not for the sake of humility, but in the name of happiness and justice.

N. A. Nekrasov’s views on the role of poetry in public life found their followers in the person of many remarkable Russian writers of the 19th and 20th centuries, affirming the inextricable connection of literature with the life of the people. It, like a mirror, reflected his fate, all life's shocks and insights. Poetry even now helps people comprehend the tragic events of our time, looking for ways to harmony with peace and happiness.

Read also...

- Tasks for children to find an extra object

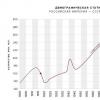

- Population of the USSR by year: population censuses and demographic processes All-Union Population Census 1939

- Speech material for automating the sound P in sound combinations -DR-, -TR- in syllables, words, sentences and verses

- The following word games Exercise the fourth extra goal