Nihilism of Evgeny Bazarov. What is nihilism? Bazarov's views. I. Checking homework

What is the essence of Bazarov's nihilism? The novel "Fathers and Sons" is directed

against the nobility. This is not the only work of Turgenev,

written in this spirit (remember, for example, “Notes of a Hunter”), but

it especially stands out because in it the writer exposed the

individual nobles, and the entire class of landowners, proved his inability

to lead Russia forward, completed his ideological defeat.

Why exactly in the early 60s of the 19th century does this appear?

work? Defeat in the Crimean War, predatory reform

1861 confirmed the decline of the nobility, its insolvency in

management of Russia. In "Fathers and Sons" it is shown that the old,

degenerating morality gives way, albeit with difficulty, to a new one,

revolutionary, progressive. The bearer of this new morality

is main character novel - Evgeny Vasilyevich Bazarov.

This young man from the commoners, seeing the decline of the dominant

classes and the state, takes the path of nihilism, that is,

denial.

What does Bazarov deny? “Everything,” he says, And everything is what

refers to the minimum human needs and to cognition

nature through personal experience, through experiments. Bazarov looks at

things from the point of view of their practical benefits. His motto: "Nature is not

a temple, but a workshop, and a person working in it.”

autocracy. But he does not look for followers and does not

fights against what it denies. This, in my opinion, is a very important feature

Bazarov's nihilism. This nihilism is directed inward, everything to Evgeniy

it doesn’t matter whether he is understood and recognized or not. Bazarov does not hide his

convictions, but he is not a preacher.

One of the features of nihilism in general is the denial of spiritual and material

values.

Bazarov is very unpretentious. He cares little about his fashionability

clothes, about the beauty of his face and body, he does not strive in any way

get some money. What he has is enough for him. Society's opinion about

he doesn't care about his financial condition. Bazarov's disdain for

material values elevates him in my eyes. This trait is

a sign of strong and smart people. Denial of spiritual values

Evgeniy Vasilyevich is disappointing. Naming spirituality

"romanticism" and "nonsense", he despises the people who bear it.

“A decent chemist is twenty times more useful than a great poet,” says

Bazarov. He mocks Arkady's father playing the cello

and those reading Pushkin, over Arkady himself, who loves nature, over

Pavel Petrovich, who threw his life at the feet of his beloved

It seems to me that Bazarov denies music, poetry, love, beauty

inertia, without really understanding these things. He discovers complete

ignorance of literature (“Nature brings the silence of sleep,” said

most likely the first in his life, did not in any way agree with the ideas

Eugene, which infuriated him. But despite the fact that

happened to him, Bazarov did not change his previous views on

love and took up arms against it even more. This is confirmation

Eugene's stubbornness and commitment to his ideas.

So, there are no values for Bazarov, and this is the reason for his

Bazarov likes to emphasize his indomitability before authorities.

He believes only in what he saw and felt himself. Although Evgeniy

declares that he does not recognize other people's opinions, he says that German

scientists are his teachers. I don't think this is a contradiction. Germans, oh

whom he says, and Bazarov himself are like-minded people, and

trust these people? Something that even a person like him has

teachers, of course: it is impossible to know everything on your own, you need to rely

on knowledge already acquired by someone.

Bazarov's mentality, constantly searching, doubting,

interrogating, can be a model for a person striving for

Bazarov is a nihilist, and this is also why we respect him. But in words

the hero of another Turgenev novel, Rudin, “skepticism has always been distinguished

sterility and impotence." These words apply to Eugene

Vasilievich. - But we need to build it. - This is no longer our business...

First you need to clear the place.

Bazarov's weakness is that, while denying, he does not offer anything in return.

Bazarov is a destroyer, not a creator. His nihilism is naive and

maximalistic, but nevertheless it is valuable and necessary. He is born

the noble ideal of Bazarov - the ideal of the strong, smart,

courageous and moral person.

Bazarov has such a peculiarity that he belongs to two different

generations. The first is the generation of the time in which he lived. Eugene

typical of this generation, like any smart commoner,

striving for knowledge of the world and confident in the degeneration of the nobility.

The second is the generation of the very distant future. Bazarov was a utopian: he

called to live not by principles, but by feelings. This is absolutely

the right path of life, but then, in the 19th century, and even now it is impossible.

Society is too corrupt to produce unspoiled people.

people and nothing more. “Fix society, and there will be no diseases.” Bazarov in

he was absolutely right about this, but he didn’t think that it wouldn’t be so easy to do it.

I am sure that a person who does not live according to the rules invented by someone

and according to his natural feelings, according to his conscience, he is a man of the future.

Therefore, Bazarov belongs to some extent to his generation

distant descendants.

Bazarov gained fame among readers thanks to his

unusual views on life, ideas of nihilism. This nihilism

immature, naive, even aggressive and stubborn, but still he is useful as

a means of making society wake up, look back and look

go ahead and think about where it is going.

The idea for Turgenev's novel "Fathers and Sons" came to the author in 1860, when he was vacationing in the summer on the Isle of Wight. The writer compiled a list of characters, among whom was the nihilist Bazarov. This article is devoted to the characteristics of this character. You will find out whether Bazarov is really a nihilist, what influenced the development of his character and worldview, and what are the positive and negative traits of this hero.

Initial author's description of Bazarov

How did Turgenev portray his hero? The author initially presented this character as a nihilist, self-confident, not without cynicism and ability. He lives small, despises the people, although he knows how to talk to them. Evgeniy does not recognize the “artistic element”. The nihilist Bazarov knows a lot, is energetic, and in essence is a “most barren subject.” Evgeny is proud and independent. Thus, at first this character was conceived as an angular and harsh figure, devoid of spiritual depth and "artistic element". Already in the process of working on the novel, Ivan Sergeevich became interested in the hero, learned to understand him, and developed sympathy for Bazarov. To some extent, he even began to justify the negative traits of his character.

Evgeny Bazarov as a representative of the generation of the 1860s

The nihilist Bazarov, despite all his spirit of denial and harshness, - typical representative generation of the 60s of the 19th century, the various democratic intelligentsia. This is an independent person who does not want to bow to authority. The nihilist Bazarov is accustomed to subjecting everything to the judgment of reason. The hero provides a clear theoretical basis for his denial. He explains social ills and imperfections of people by the character of society. Evgeniy says that moral illnesses arise from bad upbringing. A big role in this is played by all sorts of trifles that people fill their heads with from an early age. This is exactly the position that the domestic democrat educators of the 1860s adhered to.

The revolutionary nature of Bazarov's worldview

Nevertheless, in the work, criticizing and explaining the world, he tries to radically change it. Partial improvements in life, minor corrections cannot satisfy him. The hero says that it is not worth much effort to “just chat” about the shortcomings of society. He decisively demands a change in the very foundations, the complete destruction of the existing system. Turgenev saw a manifestation of revolutionism. He wrote that if Eugene is considered a nihilist, this means that he is also a revolutionary. In those days in Russia, the spirit of denial of the entire old, outdated feudal world was closely connected with the national spirit. Evgeny Bazarov's nihilism became destructive and all-encompassing over time. It is no coincidence that this hero, in a conversation with Pavel Petrovich, says that he is in vain in condemning his beliefs. After all, Bazarov’s nihilism is connected with the national spirit, and Kirsanov advocates precisely in its name.

Bazarov's denial

Turgenev, embodying the progressive traits of youth in the image of Yevgeny Bazarov, as Herzen noted, showed some injustice in relation to the experienced realistic view. Herzen believes that Ivan Sergeevich mixed it with “boastful” and “crude” materialism. Evgeny Bazarov says that he adheres to the negative direction in everything. He is “pleased to deny.” The author, emphasizing Eugene’s skeptical attitude towards poetry and art, shows a characteristic feature characteristic of a number of representatives of progressive democratic youth.

Ivan Sergeevich truthfully portrays the fact that Evgeny Bazarov, hating everything noble, extended his hatred to all poets who came from this environment. This attitude automatically extended to workers of other arts. This trait was also characteristic of many youth of that time. I.I. Mechnikov, for example, said that among the younger generation the opinion has spread that only positive knowledge can lead to progress, and art and other manifestations of spiritual life can only slow it down. That's why Bazarov is a nihilist. He believes only in science - physiology, physics, chemistry - and does not accept everything else.

Evgeny Bazarov - a hero of his time

Ivan Sergeevich Turgenev created his work even before the abolition of serfdom. At this time, revolutionary sentiments were growing among the people. The ideas of destruction and negation of the old order were brought to the fore. Old principles and authorities were losing their influence. Bazarov says that now it is most useful to deny, which is why nihilists deny. The author saw Yevgeny Bazarov as a hero of his time. After all, he is the embodiment of this denial. However, it must be said that Eugene’s nihilism is not absolute. He does not deny what has been proven by practice and experience. First of all, this applies to work, which Bazarov considers the calling of every person. The nihilist in the novel "Fathers and Sons" is convinced that chemistry is a useful science. He believes that the basis of every person’s worldview should be a materialistic understanding of the world.

Evgeniy’s attitude towards pseudo-democrats

Ivan Sergeevich does not show this hero as the leader of provincial nihilists, such as, for example, Evdokia Kukshina and the tax farmer Sitnikov. For Kukshina, even Yevgeny Bazarov is a backward woman and understands the emptiness and insignificance of such pseudo-democrats. Their environment is alien to him. Nevertheless, Evgeniy is also skeptical about popular forces. But it was on them that the revolutionary democrats of his time pinned their main hopes.

Negative aspects of Bazarov's nihilism

It can be noted that Bazarov’s nihilism, despite many positive aspects, also has negative ones. It contains the danger of discouragement. Moreover, nihilism can turn into superficial skepticism. It can even transform into cynicism. Ivan Sergeevich Turgenev, thus, astutely noted not only the positive aspects of Bazarov, but also the negative ones. He also showed that, under certain circumstances, it could develop to the extreme and lead to dissatisfaction with life and loneliness.

However, as noted by K.A. Timiryazev, an outstanding Russian democratic scientist, in the image of Bazarov, the author embodied only the traits of a type that were emerging at that time, which showed concentrated energy despite all the “minor shortcomings.” It was thanks to her that the Russian naturalist succeeded in a short time to take pride of place both at home and abroad.

Now you know why Bazarov is called a nihilist. In depicting this character, Turgenev used the technique of so-called secret psychology. Ivan Sergeevich presented Evgeny’s nature, the spiritual evolution of his hero through the life trials that befell him.

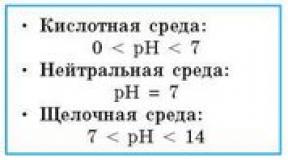

History of nihilism in Russia. Interpretation of the meaning of the word “nihilism” in different sources.” Meaning.Nihilism arises where life is devalued, where the goal is lost and there is no answer to the question about the meaning of life, about the meaning of the existence of the world itself.

We learned that the word “nihilist” in Russia has a complex history. It appeared in print in the late 20s. XIX century And at first this word was used in relation to ignoramuses who do not know anything and do not want to know. Later, in the 40s, the word “nihilist” began to be used as an expletive by reactionaries, calling their ideological enemies – materialists, revolutionaries – as such. Progressive figures did not abandon this name, but put their own meaning into it. Herzen argued that nihilism means the awakening of critical thought, the desire for accurate scientific knowledge.

Consequently, nihilism is a belief that is rigid and unyielding, based on the denial of all previous experience of human thought, on the destruction of traditions. The philosophy of nihilism cannot be positive, because... rejects everything without offering anything in return. Nihilism arises where life is devalued, where the goal is lost and there is no answer to the question about the meaning of life, about the meaning of the existence of the world itself.

Nihilism- (from Latin nihil - “nothing”) is the denial of generally accepted values: ideals, moral standards, culture, forms of social life. (Large encyclopedic dictionary)

Nihilism(from Latin nihil - “nothing”) - denial of generally accepted values: ideals, moral standards, culture, forms of social life.

Large encyclopedic dictionary

Nihilism-“an ugly and immoral teaching that rejects everything that cannot be touched.” V. Dahl

Nihilism- “naked denial of everything, logically unjustified skepticism.” Explanatory dictionary of the Russian language

Nihilism- a disease very familiar to our country, which brought troubles, suffering, and death. It turns out that Bazarov is a hero of all times and peoples, born in any country where there is no social justice and prosperity. Nihilistic philosophy is untenable because... she, denying spiritual life, denies moral principles. Love, nature, art are not just lofty words. These are the fundamental concepts underlying human morality.

A person should not rebel against those laws that are not determined by him, but dictated...Whether by God, or by nature - who knows? They are immutable. This is the law of love for life and love for people, the law of the pursuit of happiness and the law of enjoying beauty...

Bazarov's views

Scientific and philosophical views:

“There are sciences, just as there are crafts and knowledge; and science doesn’t exist at all... Studying individual personalities is not worth the trouble. All people are similar to each other both in body and soul; Each of us has a brain, spleen, heart, and lungs that are constructed in the same way; and the so-called moral qualities are the same for everyone: small modifications mean nothing. One human specimen is enough to judge all others. People are like trees in the forest; not a single botanist will study each individual birch tree.”

“Every person hangs by a thread, an abyss can open up beneath him every minute, and yet he invents all sorts of troubles for himself, ruining his life.”

“Now we generally laugh at medicine and do not bow to anyone.”

“The narrow place that I occupy is so tiny in comparison with the rest of the space where I am not and where no one cares about me; and the part of time that I manage to live is so insignificant before eternity, where I have not been and will not be... But in this atom, in this mathematical point, the blood circulates, the brain works, it also wants something... What an outrage! What nonsense!”

“...I adhere to the negative direction - due to sensation. I’m happy to deny it, my brain is designed that way – and that’s it! Why do I like chemistry? Why do you love apples? Also due to sensation. It's all one. People will never go deeper than this.”

Political Views :

“The only good thing about a Russian person is that he has a very bad opinion of himself...”

“Aristocracy, liberalism, progress, principles... - just think, how many foreign and useless words! Russian people don’t need them for nothing. We act because of what we recognize as useful. At the present time, the most useful thing is denial - we deny... Everything..."

“And then we realized that chatting, just chatting about our ulcers, is not worth the effort, that it only leads to vulgarity and doctrinaire; we saw that our wise men, the so-called progressive people, and accusers are no good, that we are engaged in nonsense, talking about some kind of art, unconscious creativity, about parliamentarism, about the legal profession and God knows what, when it comes to the essentials bread, when the grossest superstition is strangling us, when all our joint-stock companies are bursting solely because there is a shortage of honest people, when the very freedom that the government is busy about will hardly benefit us, because our peasant is happy to rob himself in order to get drunk in a tavern..."

“Moral illnesses come from bad upbringing, from all sorts of trifles that people’s heads have been stuffed with since childhood, from the ugly state of society, in a word. Correct society, and there will be no diseases... At least, with the correct structure of society, it will be completely indifferent whether a person is stupid or smart, evil or kind.”

“And I hated this last guy, Philip or Sidor, for whom I have to go out of my way and who won’t even say thank you to me... and why should I thank him? Well, he will live in a white hut, and a burdock will grow out of me, well, what then?”

Bazarov is the son of a poor district doctor. Turgenev says nothing about his student life, but one must assume that it was a poor, hard, hard life; Bazarov's father says about his son that he never took an extra penny from them; to tell the truth, much could not be taken even with the greatest desire, therefore, if old Bazarov says this in praise of his son, it means that Evgeniy Vasilyevich supported himself at the university with his own labors, interrupted himself with cheap lessons and at the same time found the opportunity to effectively prepare oneself for future activities. From this school of labor and hardship, Bazarov emerged as a strong and stern man; the course he took in natural and medical sciences developed his natural mind and weaned him from accepting any concepts or beliefs on faith; he became a pure empiricist; experience became for him the only source of knowledge, personal sensation - the only and last convincing evidence. “I stick to the negative direction,” he says, “due to sensations. I’m happy to deny it, my brain is designed that way – and that’s it! Why do I like chemistry? Why do you love apples? Also due to sensation, it is all one. People will never sink deeper than this. Not everyone will tell you this, and I won’t tell you this another time.” As an empiricist, Bazarov recognizes only what can be felt with his hands, seen with his eyes, put on his tongue, in a word, only what can be witnessed by one of the five senses. He reduces all other human feelings to activity nervous system; As a result of this enjoyment of the beauties of nature, music, painting, poetry, love, women do not seem at all higher and purer to him than the enjoyment of a hearty dinner or a bottle of good wine. What enthusiastic young men call ideal does not exist for Bazarov; he calls all this “romanticism”, and sometimes instead of the word “romanticism” he uses the word “nonsense”. Despite all this, Bazarov does not steal other people’s scarves, does not extract money from his parents, works diligently and is not even averse to doing something worthwhile in life.

You can be indignant at people like Bazarov as much as you like, but recognizing their sincerity is absolutely necessary. These people can be honest or dishonest, civic leaders or outright swindlers, depending on circumstances and personal tastes. Nothing but personal taste prevents them from killing and robbing, and nothing but personal taste encourages people of this caliber to make discoveries in the field of science and social life. Bazarov won’t steal a handkerchief for the same reason why he won’t eat a piece of rotten beef. If Bazarov was dying of hunger, he would probably do both. The painful feeling of unsatisfied physical need would have overcome his aversion to the foul smell of decaying meat and to the secret encroachment on someone else's property. In addition to direct attraction, Bazarov has another leader in life - calculation. When he is ill, he takes medicine, although he does not feel an immediate desire for castor oil or assafetida. He acts this way out of calculation: at the cost of a small nuisance, he buys greater convenience in the future or getting rid of a big nuisance. In a word, he chooses the lesser of two evils, although he does not feel any attraction to the lesser. For mediocre people, this kind of calculation for the most part turns out to be untenable; Out of calculation, they are cunning, mean, steal, get confused and in the end remain fools. Very smart people do things differently; they understand that being honest is very profitable and that from simple lies to murder is dangerous and, therefore, inconvenient. Therefore very smart people They can be honest in their calculations and act honestly where narrow-minded people will wag and throw loops. Working tirelessly, Bazarov obeyed his immediate desire, taste and, moreover, acted according to the most correct calculations. If he had sought patronage, bowed down, and been mean, instead of working and holding himself proudly and independently, then he would have acted imprudently. Careers made by one's own head are always stronger and wider than careers made by low bows or the intercession of an important uncle. Thanks to the last two means, one can get into the provincial or capital aces, but thanks to the grace of these means, no one since the world stood has managed to become either Washington, or Garibaldi, or Copernicus, or Heinrich Heine. Even Herostratus made his career on his own and ended up in history not through patronage. As for Bazarov, he does not aim to become a provincial ace: if his imagination sometimes depicts a future for him, then this future is somehow indefinitely broad; he works without a goal, to obtain his daily bread or out of love for the process of work, and yet he vaguely feels from the amount of his own strength that his work remains without a trace and will lead to something. Bazarov is extremely proud, but his pride is invisible precisely because of his enormity. He is not interested in the little things that make up everyday human relationships; he cannot be offended by obvious neglect, he cannot be pleased with signs of respect; he is so full of himself and stands so unshakably high in his own eyes that he becomes almost completely indifferent to the opinions of other people. Uncle Kirsanov, who is close to Bazarov in mentality and character, calls his pride “satanic pride.” This expression is very well chosen and perfectly characterizes our hero. Indeed, only an eternity of ever-expanding activity and ever-increasing pleasure could satisfy Bazarov, but, unfortunately for himself, Bazarov does not recognize the eternal existence of the human person. “Well, here’s an example,” he says to his comrade Kirsanov, “you said today, passing by the hut of our elder Philip, “it’s so nice, white,” you said: Russia will then reach perfection when the last man has the same room , and each of us must contribute to this... And I hated this last man, Philip or Sidor, for whom I have to bend over backwards and who won’t even say thank you to me... And why should I thank him? Well, he will live in a white hut, and a burdock will grow out of me; Well, what next?”

Bazarov everywhere and in everything acts only as he wants or as it seems profitable and convenient to him. It is controlled only by personal whim or personal calculations. Neither above himself, nor outside himself, nor within himself does he recognize any regulator, any moral law, any principle. There is no lofty goal ahead; there is no lofty thought in the mind, and despite all this, the strength is enormous. - But this is an immoral person! Villain, freak! – I hear exclamations from indignant readers from all sides. Well, okay, villain, freak: scold him more, persecute him with satire and epigrams, indignant lyricism and indignant public opinion, the fires of the Inquisition and the axes of executioners - and you will not poison, you will not kill this freak, you will not put him in alcohol to a surprisingly respectable public . If bazaarism is a disease, then it is a disease of our time, and we have to suffer through it, despite any palliatives and amputations. Treat bazaarism however you like - it’s your business; but to stop - do not stop; it's the same cholera.

The disease of the century first of all sticks to people whose mental powers are above the general level. Bazarov, obsessed with this disease, is distinguished by a remarkable mind and, as a result, makes a strong impression on the people who encounter him. “A real person,” he says, “is one about whom there is nothing to think, but whom one must obey or hate.” Bazarov himself fits the definition of a real person; he constantly immediately captures the attention of the people around him; some of them he intimidates and pushes away; subjugates others not so much with arguments as with the direct strength, simplicity and integrity of his concepts. As a remarkably intelligent person, he had no equal. “When I meet a person who would not give up in front of me,” he said with emphasis, “then I will change my opinion about myself.”

He looks down on people and rarely even bothers to hide his half-contemptuous, half-patronizing attitude towards those people who hate him and those who obey him. He doesn't love anyone; without breaking existing connections and relationships, he at the same time will not take a single step to re-establish or maintain these relationships, will not soften a single note in his stern voice, will not sacrifice a single sharp joke, not a single eloquent word.

He does this not in the name of principle, not in order to be completely frank at every given moment, but because he considers it completely unnecessary to embarrass his person in anything, for the same reason for which Americans lift their legs on the backs of chairs and spitting tobacco juice on the parquet floors of luxurious hotels. Bazarov does not need anyone, is not afraid of anyone, does not love anyone, and as a result, does not spare anyone. Like Diogenes, he is ready to live almost in a barrel and for this he gives himself the right to speak harsh truths to people’s faces for the reason that he likes it. In Bazarov’s cynicism, two sides can be distinguished - internal and external: cynicism of thoughts and feelings and cynicism of manners and expressions. An ironic attitude towards feelings of all kinds, towards daydreaming, towards lyrical impulses, towards outpourings is the essence of internal cynicism. The rude expression of this irony, the causeless and aimless harshness in address refer to external cynicism. The first depends on the mindset and the general worldview; the second is determined by purely external conditions of development, the properties of the society in which the subject in question lived. Bazarov's mocking attitude towards the soft-hearted Kirsanov stems from the basic properties of the general Bazarov type. His rough clashes with Kirsanov and his uncle constitute his personal identity. Bazarov is not only an empiricist - he is, moreover, an uncouth bursh, who knows no other life than the homeless, working, and sometimes wildly riotous life of a poor student. Among Bazarov’s admirers there will probably be people who will admire his rude manners, traces of Bursat life, will imitate his rude manners, which in any case constitute a disadvantage and not an advantage, will even, perhaps, exaggerate his angularity, baggyness and sharpness. Among Bazarov’s haters there will probably be people who will pay special attention to these unsightly features of his personality and reproach them to the general type. Both will be mistaken and will reveal only a deep misunderstanding of the real matter.

You can be an extreme materialist, a complete empiricist, and at the same time take care of your toilet, treat your acquaintances with refinement and politeness, be an amiable interlocutor and a perfect gentleman.

It occurred to Turgenev to choose an uncouth person as a representative of Bazarov’s type; he did so and, of course, while drawing his hero, he did not hide or paint over his angularities; Turgenev’s choice can be explained by two different reasons: firstly, the personality of a person who mercilessly and with complete conviction denies everything that others recognize as lofty and beautiful is most often developed in the gray environment of working life; from harsh work, hands become coarse, manners become coarser, feelings become coarser; a person becomes stronger and drives away youthful daydreaming, gets rid of tearful sensitivity; You can’t daydream while working, because your attention is focused on the task at hand; and after work you need rest, you need to really satisfy your physical needs, and a dream will come to mind. A person is accustomed to looking at a dream as a whim, characteristic of idleness and lordly tenderness; he begins to consider moral suffering as dreamy; moral aspirations and exploits - invented and absurd. For him, a working man, there is only one, ever-repeating concern: today he must think about not going hungry tomorrow. This simple, menacing in its prostate concern obscures from him the rest, secondary anxieties, squabbles and worries of life; in comparison with this concern, various unresolved questions, unexplained doubts, uncertain relationships that poison the lives of wealthy and idle people seem small, insignificant, artificially created.

Thus, the proletarian worker, by the very process of his life, regardless of the process of reflection, reaches practical realism; due to lack of time, he forgets to dream, to chase an ideal, to strive in an idea for an unattainably high goal. By developing energy in the worker, work accustoms him to bring action closer to thought, an act of will to an act of mind. A person who is accustomed to relying on himself and his own strengths, who is accustomed to carrying out today what was planned yesterday, begins to look with more or less obvious disdain at those people who, dreaming of love, of useful activity, of the happiness of the entire human race, does not know how to lift a finger in order to in any way improve his own, extremely uncomfortable situation. In a word, a man of action, be he a physician, a craftsman, a teacher, even a writer (one can be a writer and a man of action at the same time), feels a natural, insurmountable aversion to phrasing, to wasting words, to sweet thoughts, to sentimental aspirations and in general to any claims that are not based on real, tactile force. This kind of aversion to everything detached from life and evaporating in sounds is the fundamental property of people of the Bazarov type. This fundamental property is developed precisely in those diverse workshops in which a person, refining his mind and straining his muscles, fights with nature for the right to exist in this world. On this basis, Turgenev had the right to take his hero in one of these workshops and bring him in a working apron, with unwashed hands and a gloomy, preoccupied look into the company of fashionable gentlemen and ladies. But justice prompts me to express the assumption that the author of the novel “Fathers and Sons” acted in this way not without insidious intent. This insidious intent constitutes the secondary cause that I mentioned above. The fact is that Turgenev obviously does not favor his hero. His soft, loving nature, striving for faith and sympathy, is jarred by corrosive realism; his subtle aesthetic sense, not without a significant dose of aristocracy, is offended by even the slightest glimpses of cynicism; he is too weak and impressionable to endure bleak denial; he needs to come to terms with existence, if not in the realm of life, then at least in the realm of thought, or rather, dreams. Turgenev, like a nervous woman, like a “don’t touch me” plant, shrinks painfully from the slightest contact with a bouquet of bazaarism.

Feeling, therefore, an involuntary antipathy to this line of thought, he brought it before the reading public in a perhaps ungraceful copy. He knows very well that there are a lot of fashionable readers in our public, and, counting on the sophistication of their aristocratic taste, he does not spare rough colors, with an obvious desire to drop and vulgarize, along with the hero, that store of ideas that constitutes the general affiliation of the type. He knows very well that most of his readers will only say about Bazarov that he is poorly brought up and that he cannot be allowed into a decent drawing room; they will not go further or deeper; but when speaking with such people, a gifted artist and an honest man must be extremely careful out of respect for himself and for the idea that he defends or refutes. Here you need to keep your personal antipathy in check, which under certain conditions can turn into involuntary slander against people who do not have the opportunity to defend themselves with the same weapons.

Arkady Nikolaevich Kirsanov is a young man, not stupid, but completely devoid of mental originality and constantly in need of someone's intellectual support. He is probably five years younger than Bazarov and in comparison seems like a completely unfledged chick, despite the fact that he is about twenty three years and that he completed a course at the university. Reverently before his teacher, Arkady rejects authority with pleasure; he does this from someone else's voice, thus not noticing the internal contradiction in his behavior. He is too weak to stand on his own in that cold atmosphere of sober rationality in which Bazarov breathes so freely; he belongs to the category of people who are always looked after and always do not notice the care over themselves. Bazarov treats him patronizingly and almost always mockingly; Arkady often argues with him, and in these disputes Bazarov gives full rein to his weighty humor. Arkady does not love his friend, but somehow involuntarily submits to the irresistible influence of a strong personality, and, moreover, imagines that he deeply sympathizes with Bazarov’s worldview. His relationship with Bazarov is purely head-to-head, made to order; he met him somewhere in a student circle, became interested in the integrity of his views, submitted to his strength and imagined that he deeply respected him and loved him from the bottom of his heart. Bazarov, of course, did not imagine anything and, without embarrassment at all, allowed his new proselyte to love him, Bazarov, and maintain a constant relationship with him. He went with him to the village not in order to please him, and not in order to meet the family of his betrothed friend, but simply because it was on the way, and, finally, why not live as a guest for two weeks a decent person, in the village, in the summer, when there are no distracting activities or interests?

The village to which our young people arrived belongs to Arkady’s father and uncle. His father, Nikolai Petrovich Kirsanov, is a man in his forties; In terms of character, he is very similar to his son. But Nikolai Petrovich has much more correspondence and harmony between his mental beliefs and natural inclinations than Arkady. As a soft, sensitive and even sentimental person, Nikolai Petrovich does not rush towards rationalism and calms down on such a worldview that gives food to his imagination and pleasantly tickles his moral sense. Arkady, on the contrary, wants to be the son of his century and directs Bazarov’s ideas to himself, which absolutely cannot merge with him. He is on his own, and ideas dangle on their own, like an adult’s frock coat put on a ten-year-old child. Even that childish joy that is revealed in a boy when he is jokingly promoted to the big ones, even this joy, I say, is noticeable in our young thinker from someone else’s voice. Arkady flaunts his ideas, tries to draw the attention of others to them, thinks to himself: “What a great guy I am!” and, alas, like a small, unreasonable child, sometimes he screws up and comes to an obvious contradiction with himself and his false beliefs.

Arkady's uncle, Pavel Petrovich, can be called a Pechorin of small proportions: in his lifetime he chewed and fooled around, and, finally, he got tired of everything; he failed to settle in, and this was not in his character; having reached the time when, as Turgenev put it, regrets are like hopes and hopes are like regrets, former lion retired to his brother in the village, surrounded himself with elegant comfort and turned his life into a calm stay. An outstanding upbringing from Pavel Petrovich’s former noisy and brilliant life was a strong feeling for one high-society woman, a feeling that brought him a lot of pleasure and, as is almost always the case, a lot of suffering. When Pavel Petrovich’s relationship with this woman ended, his life was completely empty.

“Like a poisoned man, he wandered from place to place,” says Turgenev, “he still traveled, he retained all the habits of a secular man, he could boast of two or three new victories; but he no longer expected anything special either from himself or from others and did nothing; he grew old and gray; sitting in the club in the evenings, being biliously bored, indifferently arguing in single society became a necessity for him - as you know, a bad sign. Of course, he didn’t even think about marriage. Ten years passed in this way, colorless, fruitless and quickly, terribly quickly. Nowhere does time run faster than in Russia: in prison they say it runs even faster.”

As a bilious and passionate person, gifted with a flexible mind and strong will, Pavel Petrovich differs sharply from his brother and nephew. He does not succumb to the influence of others; he subjugates the people around him and hates those people in whom he encounters rebuff. To tell the truth, he has no convictions, but he does have habits that he values very much. Out of habit, he talks about the rights and duties of the aristocracy and, out of habit, proves the need for “principles” in disputes. He is accustomed to the ideas on which society rests, and stands for those ideas as for his own comfort. He cannot stand anyone refuting these concepts, although in essence he has no heartfelt affection for them. He argues with Bazarov much more energetically than his brother, and yet Nikolai Petrovich suffers much more sincerely from his merciless denial. At heart, Pavel Petrovich is the same skeptic and empiricist as Bazarov himself; in practical life he has always acted and acts as he pleases, but in the realm of thought he does not know how to admit this to himself and therefore verbally supports doctrines that his actions constantly contradict. The uncle and nephew should exchange their beliefs among themselves, because the first mistakenly ascribes to himself faith in principles, the second, in the same way, mistakenly imagines himself as an extreme skeptic and a bold rationalist. Pavel Petrovich begins to feel a strong antipathy towards Bazarov from the first meeting. Bazarov's plebeian manners outrage the retired dandy; his self-confidence and unceremoniousness irritate Pavel Petrovich as a lack of respect for his graceful person. Pavel Petrovich sees that Bazarov will not yield to him dominance over himself, and this arouses in him a feeling of annoyance, which he seizes on as entertainment in the midst of deep ancient boredom. Hating Bazarov himself, Pavel Petrovich is indignant at all his opinions, finds fault with him, forcibly challenges him to an argument and argues with that zealous passion that idle and bored people usually display.

What does Bazarov do among these three individuals? Firstly, he tries to pay as little attention to them as possible and spends most of his time at work; wanders around the surrounding area, collecting plants and insects, cutting up frogs and making microscopic observations; he looks at Arkady as a child, at Nikolai Petrovich as a good-natured old man, or, as he puts it, an old romantic. He is not entirely friendly towards Pavel Petrovich; he is outraged by the element of lordship in him, but he involuntarily tries to hide his irritation under the guise of contemptuous indifference. He doesn’t want to admit to himself that he can be angry with the “district aristocrat,” but meanwhile his passionate nature takes its toll; He often passionately objects to Pavel Petrovich’s tirades and does not suddenly manage to control himself and withdraw into his mocking coldness. Bazarov does not like to argue or speak out at all, and only Pavel Petrovich partly has the ability to provoke him into a meaningful conversation. These two strong characters act hostile to each other; Seeing these two people face to face, one can imagine the struggle taking place between two generations immediately following one another. Nikolai Petrovich, of course, is not capable of entering the fight against family despotism; but Pavel Petrovich and Bazarov could, under certain conditions, appear as bright representatives: the first - of the constraining, chilling force of the past, the second - of the destructive, liberating force of the present.

Bazarov is lying - this, unfortunately, is fair. He bluntly denies things he does not know or does not understand; poetry, in his opinion, is nonsense; reading Pushkin is wasted time; making music is funny; enjoying nature is absurd. It may very well be that he, a person worn out by work life, has lost or has not had time to develop in himself the ability to enjoy the pleasant stimulation of the visual and auditory nerves, but it does not follow from this that he has any reasonable grounds to deny or ridicule this ability in others. To cut other people into the same standard as yourself means to fall into narrow mental despotism. To deny completely arbitrarily one or another natural and truly existing need or ability in a person means moving away from pure empiricism.

Bazarov's passion is very natural; it is explained, firstly, by the one-sidedness of development, and secondly, by the general character of the era in which he had to live. Bazarov has a thorough knowledge of natural and medical sciences; with their assistance, he knocked all prejudices out of his head; then he remained an extremely uneducated man; he had heard something about poetry, something about art, but did not bother to think and passed judgment on subjects unfamiliar to him. This arrogance is characteristic of us in general; she has her own the good side like mental courage, but, of course, sometimes it leads to gross mistakes. The general character of the era lies in a practical direction; We all want to live and adhere to the rule that the nightingale is not fed fables. People who are very energetic often exaggerate the trends that dominate society; on this basis, Bazarov’s too indiscriminate denial and the very one-sidedness of his development stand in direct connection with the prevailing desires for tactile benefit. We were tired of the phrases of the Hegelists, we became dizzy from hovering in the sky-high heights, and many of us, having sobered up and descended to earth, went to extremes and, banishing daydreaming, together with it began to pursue simple feelings and even purely physical sensations, such as the enjoyment of music . There is no great harm in this extreme, but it doesn’t hurt to point it out, and calling it funny does not mean joining the ranks of obscurantists and old romantics.

“And nature is nothing? - said Arkady, thoughtfully looking into the distance at the colorful fields, beautifully and softly illuminated by the already low sun.

And nature is nothing in the sense in which you now understand it. Nature is not a temple, but a workshop, and man is a worker in it.”

In these words, Bazarov’s denial turns into something artificial and even ceases to be consistent. Nature is a workshop, and man is a worker in it - I am ready to agree with this idea; but, developing this idea further, I in no way come to the results that Bazarov comes to. A worker needs to rest, and rest cannot be limited to one heavy sleep after tiring work. A person needs to be refreshed by pleasant impressions, and life without pleasant impressions, even if all essential needs are satisfied, turns into unbearable suffering. If a worker found pleasure in lying on his back in his free hours and staring at the walls and ceiling of his workshop, then all the more so would any sensible person say to him: gaze, dear friend, gaze as much as your heart desires; will not harm your health, but work time You won’t stare, so as not to make mistakes. Pursuing romanticism, Bazarov with incredible suspicion looks for it where it has never been. Arming himself against idealism and smashing its castles in the air, he sometimes becomes an idealist himself, i.e. begins to prescribe laws for a person on how and what he should enjoy and to what standard he should adjust his personal sensations. Telling a person: don’t enjoy nature is the same as telling him: mortify your flesh. The more harmless sources of pleasure there are in life, the easier it will be to live in the world, and the whole task of our time is to reduce the amount of suffering and increase the amount of pleasure.

In Bazarov's relationship with to the common people One must notice first of all the absence of any pretentiousness and any sweetness. The people like it, and therefore the servants love Bazarov, the children love him, despite the fact that he does not treat them with almonds at all and does not lavish them with money or gingerbread. Having noticed in one place that they love Bazarov simple people, Turgenev says in another place that the men look at him like a fool. These two testimonies do not contradict each other at all. Bazarov behaves simply with the peasants, does not reveal either lordship or a feigned desire to imitate their speech and teach them wisdom, and therefore the peasants, speaking to him, are not timid or embarrassed; but, on the other hand, Bazarov, in terms of address, language, and concepts, is completely at odds with both them and those landowners whom the peasants are accustomed to seeing and listening to. They look at him as a strange, exceptional phenomenon, neither this nor that, and will look at gentlemen like Bazarov in this way until there are no more of them and until they have time to take a closer look at them. The men have a heart for Bazarov, because they see him as simple and smart person, but at the same time this person is a stranger to them, because he does not know their way of life, their needs, their hopes and fears, their concepts, beliefs and prejudices.

After his failed romance with Odintsova, Bazarov again comes to the village to the Kirsanovs and begins to flirt with Fenechka, Nikolai Petrovich’s mistress. He likes Fenechka as a plump, young woman; She likes him as a kind, simple and cheerful person. One fine July morning he manages to imprint a full kiss on her fresh lips; she resists weakly, so he manages to “renew and prolong his kiss.” At this point, his love affair ends: he, apparently, had no luck at all that summer, so not a single intrigue was brought to a happy ending, although they all began with the most favorable omens.

At the end of the novel, Bazarov dies; his death is an accident; he dies from surgical poisoning, i.e. from a small cut made during the dissection of the corpse. This event is not connected with the general thread of the novel; it does not follow from previous events, but it is necessary for the artist to complete the character of his hero. The novel takes place in the summer of 1859; during 1860 and 1861, Bazarov could not have done anything that would show us the application of his worldview in life; he would still be cutting frogs, fiddling with a microscope and, mocking various manifestations of romanticism, would enjoy the blessings of life to the best of his ability and ability. All this would be just the makings; it will be possible to judge what will develop from these inclinations only when Bazarov and his peers are fifty years old and when they are replaced by a new generation, which in turn will be critical of their predecessors. People like Bazarov are not completely defined by one episode snatched from life. This kind of episode gives us only a vague idea that colossal powers lurk in these people. How will these forces be expressed? This question can only be answered by the biography of these people or the history of their people, and biography, as is known, is written after the death of the figure, just as history is written when the event has already occurred. From the Bazarovs, under certain circumstances, great historical figures are developed; such people remain young, strong and fit for any work for a long time; they do not fall into homogeneity, do not become attached to theory, do not grow into special studies; they are always ready to exchange one area of activity for another, broader and more entertaining; they are always ready to leave the classroom and laboratory; These are not workers; delving into careful research into special issues of science, these people never lose sight of the great world that contains their laboratory and themselves, with all their science and with all their instruments and apparatus; when life seriously stirs their brain nerves, then they will throw away the microscope and the scalpel, then they will leave some scientific research about bones or membranes unfinished. Bazarov will never become a fanatic, a priest of science, will never elevate it to an idol, will never doom his life to its service; constantly maintaining a skeptical attitude towards science itself, he will not allow it to acquire independent significance; he will engage in it either in order to give work to his brain, or in order to squeeze out of it immediate benefit for himself and for others. He will practice medicine partly to pass the time, partly as a bread and useful craft. If another occupation presents itself, more interesting, more profitable, more useful, he will leave medicine, just as Benjamin Franklin left the printing press. Bazarov is a man of life, a man of action, but he will get down to business when he sees the opportunity to act mechanically. He will not be captivated by deceptive forms; external improvements will not overcome his stubborn skepticism; he will not mistake a random thaw for the onset of spring and will spend his entire life in the laboratory unless significant changes occur in the consciousness of our society. If the desired changes occur in consciousness, and consequently in the life of society, then people like Bazarov will be ready, because the constant work of thought will not allow them to become lazy, stale and rusty, and constantly awake skepticism will not allow them to become fanatics of their specialty or lukewarm followers of a one-sided doctrine. Who will dare to guess the future and throw hypotheses to the wind? Who will decide to complete a type that is just beginning to take shape and take shape and which can only be completed by that time and events? Unable to show us how Bazarov lives and acts, Turgenev showed us how he dies. This is enough for the first time to form an idea about Bazarov’s forces, about those forces whose full development could only be indicated by life, struggle, actions and results. That Bazarov is not a phrase-monger - anyone will see this by peering into this personality from the very first minute of her appearance in the novel. That the denial and skepticism of this person are conscious and felt, and not put on for whims and for greater importance - every impartial reader is convinced of this by immediate sensation. Bazarov has strength, independence, energy that phrase-mongers and imitators do not have. But if someone wanted not to notice and feel the presence of this force in him, if someone wanted to question it, then the only fact that solemnly and categorically refuting this absurd doubt would be Bazarov’s death. His influence on the people around him does not prove anything. It is not difficult to make a strong impression on people like Arkady, Nikolai Petrovich, Vasily Ivanovich and Arina Vlasyevna. But looking into the eyes of death, foreseeing its approach, without trying to deceive yourself, remaining true to yourself until the last minute, not weakening or becoming cowardly is a matter of strong character. To die the way Bazarov died is the same as accomplishing a great feat; this feat remains without consequences, but the dose of energy that is spent on the feat, on a brilliant and useful task, is spent here on a simple and inevitable physiological process. Because Bazarov died firmly and calmly, no one felt either relief or benefit, but such a person who knows how to die calmly and firmly will not retreat in the face of an obstacle and will not cower in the face of danger.

Meanwhile, Bazarov wants to live, it’s a pity to say goodbye to self-consciousness, to his thought, to his strong personality, but this pain of parting with a young life and with unworn forces is expressed not in soft sadness, but in bilious, ironic frustration, in a contemptuous attitude towards oneself , as to a powerless creature, and to that rough, absurd accident that crushed and crushed him. A nihilist remains true to himself until the very last minute.

As a physician, he saw that infected people always die, and he does not doubt the immutability of this law, despite the fact that this law condemns him to death. In the same way, at a critical moment he does not change his gloomy worldview for another more joyful one; as a physician and as a person, he does not console himself with mirages.

If a person, weakening control over himself, becomes better and more humane, then this serves as energetic proof of the integrity, completeness and natural richness of nature. Bazarov's rationality was a forgivable and understandable extreme in him; this extreme, which forced him to be wise about himself and break himself, would have disappeared under the influence of time and life; she disappeared in the same way during the approach of death. He became a man, instead of being the embodiment of the theory of nihilism, and, as a man, he expressed the desire to see the woman he loved.

Used Books:

1. I.S. Turgenev "Fathers and Sons". 1975

2. I.S. Turgenev “On the Eve”, “Fathers and Sons”, prose poems. 1987

3. Large educational reference book on Russian literature of the 19th century. 2000

Ivan Turgenev belongs to the category of writers who made a significant contribution to the development of Russian literature. The most famous of his major works is the novel “Fathers and Sons,” which provoked heated controversy in society immediately after its publication. Turgenev foresaw such a reaction from the reading public and even desired it, specially dedicating a separate publication to Belinsky (thus challenging the liberal intelligentsia): “I don’t know what success will be, Sovremennik will probably shower me with contempt for Bazarov - and will not believe that “all the time I was writing, I felt an involuntary attraction to him,” the author wrote in his diary on July 30, 1861. It was the main character and his views that caused fierce debate among Turgenev's contemporaries.

The main idea of many of Turgenev's novels is the expression of the characteristics of the time through typical characters. The focus is on the socio-historical type that represents the dynamic beginning of the era. The hero comes into a traditional conservative society and destroys its stereotypes, becoming a victim of the mission that is entrusted to him due to circumstances. Its historical task is to shake the established routine of life, introduce new trends and change the existing way of life. Bazarov is a commoner (from the family of an ordinary rural doctor) who rises up the social ladder thanks to his intellectual abilities and personal achievements, and not to title, origin or wealth. Thus, the conflict in the novel can be described as “a commoner in a noble nest,” that is, the opposition of a working man to an idle noble society. Such a hero is always alone, his path is gloomy and thorny, and the outcome is certainly tragic. He alone cannot turn the world upside down, so his good intentions are always doomed, he is seemingly helpless, inactive, even pitiful. But his mission is to snatch the next generation from the pool of indifference of their grandfathers, from their moral and mental stagnation, and not to change his generation overnight. This is a realistic novel, the plot develops according to the laws of life itself.

If Bazarov is the bearer of historical progress, why does he deny everything? Who is a nihilist? Nihilism is a worldview position that questions generally accepted values, ideals, moral and cultural norms. The hero denies even love, so his nihilism can be called grotesque. Turgenev deliberately thickens the colors in order to enhance the drama of the work and lead Bazarov through the “copper pipes” - a mutual feeling for Odintsova. This is how he tests the hero (this is his favorite technique) and evaluates the whole generation. Despite his total denial, Bazarov is capable of experiencing strong passion for a woman, he is real, his impulses and thoughts are natural. Unlike the secondary characters, who fake and hide behind nihilism in order to impress, Bazarov is sincere both in his hatred of the old order and in his love for Odintsova. He contradicts himself, falling in love, but discovers new facets of existence, learns its fullness. He passed the test. Even Turgenev (a nobleman, an official, a representative of a more conservative camp than Belinsky, for example) developed sympathy for his hero.

This is how the author wrote about Bazarov: “... if he is called a nihilist, then it should be read: a revolutionary.” That is, in Turgenev’s understanding, a nihilist is a revolutionary, a person who opposes himself to the existing social order. The hero really rejects the institutions and ideological concepts approved and sanctified by the state. He is a materialist who sets himself the goal of serving the progress of society and, to the best of his ability, clearing it of prejudices. Truly a revolutionary feat! Bazarov dooms himself to misunderstanding and loneliness, causes fear and alienation in people, and limits his life to service. The fact that he so persistently denies everything is just a desperate protest of a man who is “alone in the field.” Excessive radicalism is like a loud cry crying in the desert. This is the only way he will be heard, the only way the next generation will understand him. He will have to implement everything that Bazarov will not have time to do. As befits a mission, he will die young, leaving a kind of “apostles” to instill new ideas and lead people to the future.