Princess Olga Romanova. Is it easy to be a princess? Department of Culture of the Voronezh Region

Princess Olga Andreevna

The great-great-granddaughter of Nicholas I and great-niece of the last Russian Tsar Nicholas II lives on the 13th-century family estate of Provender in Kent, filled with unique items belonging to many generations of the Romanovs, family photographs and documents related to Russian history. She is writing a book based on the memoirs of her father, Prince Andrei Alexandrovich. He is the patron of the Russian Debutante Ball.

Often loving fathers They call their little daughters “my princess.” This has nothing to do with the title. But you have this title. How kindly did your father treat you as a child? Calling you a “princess” is simply stating a fact.

My father never called me princess. Always only “my dear”, “my darling”, “my honey-bunny”. And very often - “baby”. Even when he introduced me. I was always a little girl for him, the youngest daughter. His children from his first marriage are much older than me. By the age of 26, he already had three children, and when I was born, he was 54 years old. By the way, he never called me Olga. I didn't like the name Olga; in my opinion, it wasn't English enough. I would rather be Mary, Elizabeth or Alexandra. There are many different options. Alexandra, for example, is Alex, Sandra, and Sasha. And Olga is just Olga and that’s it.

I read that you received a private home education, typical of the House of Romanov. What did this education include?

When my parents got married, they began to live on my mother's estate, Provender, in the county of Kent - I was born there, grew up and now live there. At the age of 8, my mother and her brothers - seven and six years old - were sent to boarding school, because my grandmother traveled a lot, wrote books and had no time to take care of children. My mother had terrible memories of this school, and since I was their late and only child, she insisted on my home education. Dad didn't mind, he just adored me. Until I was 12 years old, I was educated at home. In addition to teachers in academic subjects, there were teachers in tennis, ballet, and horse riding. A ballroom dancing All my local friends came to study with me.

Prince Andrei Alexandrovich - father of Olga Andreevna

As far as I understand, Russian language lessons were not part of your home education program. Why?

The father spoke five languages fluently and communicated in Russian with his older children. But not with me. When they came to us cousins, uncles, aunts, they spoke only Russian, and my mother and I sat quietly in a corner and listened. I think it's because of the tragic revolution. Father tried not to forget Russia and everything connected with it, but rather not to let it into our lives. Unfortunately, he spoke little about that period of his life. He was only 21 years old when his family was forced to leave Russia in 1918. During the revolution, they were in Crimea, in Ai-Todor - the estate of his father (Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich). It is not far from Yalta. A small path connected the estate and the Livadia Palace - the summer residence of Nicholas II. Grandmother Princess Ksenia Alexandrovna was the sister of Nicholas II. Along this path one could easily get to the palace - they spent a lot of time together.

Father loved Ai-Todor very much. The children and their nannies lived there in a large house, and their parents lived nearby in a smaller house. Separate from children. The huge house was surrounded by vineyards leading down to the sea. Grandfather owned 90% of all vineyards in Crimea. They made wonderful wine there.

Did your father suffer from nostalgia for Russia?

My father missed Russia very much and always said that someday the situation would change and it would be possible to return. He wanted to go with all his heart, but was very afraid for himself and his family. Going there was a huge risk. After the revolution, two of my great-uncles were assassinated outside Russia. My parents asked me not to go to Russia. We were very nervous about this. The first time I went to Russia was in 1998 for the reburial ceremony of the remains of the royal family, along with my son and fifty-six other Romanovs.

When they left Russia, were they able to take anything with them that was later inherited by you and that you now keep?

The British Royal Navy battleship Marlborough was sent by King George V of Great Britain to evacuate members of the Romanov family. On board it, my father and his first wife, my grandfather ( Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich), grandmother (Grand Duchess Ksenia Alexandrovna), great-grandmother (Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna) and many other family members. Surprisingly, they were able to take with them even more than they expected. Much that was taken out of Russia by Maria Dagmar's great-grandmother, Maria Feodorovna, went to her native Denmark, where she settled in the Vidøre villa, not far from Copenhagen. Much later, we moved here some of the furniture, a collection of porcelain, paintings and family photographs. In the library in my Provender house there is a table made especially for Maria Dagmar, brought from Copenhagen. And in the leather chests that belonged to my father, with which he left Russia, I keep blankets and pillows. They are still in excellent condition.

What about family jewelry? Did you get anything from them?

I would really like to, but unfortunately not. The great-grandmother had to sell or exchange many jewelry, Faberge eggs and other valuables for food. They had no money at all. Some of the remainder went to the daughters. My father did not get any of the jewelry. But we have preserved many icons.

Andrey Alexandrovich with his sister Irina Alexandrovna, mother Ksenia Alexandrovna and aunt Olga Alexandrovna in Videra. 1926

After the revolution in Russia, many Romanovs were shot by the Bolsheviks, but mostly representatives of the Russian Imperial House were able to leave the country. Finding themselves in exile, they settled in Europe, some moved to North America and Australia. After World War II, contacts between members of the clan weakened significantly. Then the idea of the Association arose in order to be able to communicate more often and monitor the successes of family members. In 1979, my father was the oldest of the Romanovs and it was he who was invited to lead the Association. But he refused - at 82 years old it is quite difficult to take on such responsibility. It is difficult to say exactly how many family members are left; many are no longer alive. The Association last met in 2001. The Romanovs are strange people; when they meet, they love each other immensely, but once they separate, they may not make themselves known at all for several years.

How did your parents meet? Is there a romantic story about how your parents met?

It's not like the story was very romantic. The parents first met at the Finnish Embassy in London in the mid-20s. My grandmother was friends with the Finnish ambassador, and my mother sometimes helped greet guests at receptions at the embassy. The father was with his first wife, they then met many times in other places. After the death of his father's first wife, the parents met again in Scotland, at a reception at the royal Balmoral Castle and soon got married.

Your mother's maiden name is MacDougall, there is an auction house in London specializing in Russian art with that name. Are these your maternal relatives?

My mother's name was Nadine McDougall. I'm distantly related to William McDougall, but I've never met him.

I know that you are the patron of several balls held in London. Remember the ball where you made your debut?

I am the patron of four balls and not only in London. Russian Summer Ball - my grandmother Ksenia Alexandrovna was the patron of this ball, Cossack Ball, The Russian Debutant Ball in London - this is in London, and the Russian Ball in Bulgaria is held in Sofia. Every debutant remembers his first ball. That is why it gives me such pleasure to be a patron and to be present at the Debutante Ball. This year the fourth Debutante Ball will be held in London in November. My very first ball was at the German embassy in London in the late 60s. It was terribly interesting. Then I spent the entire season, eight months, in a white dress. My own ball for 400 people was held at the Dorchester Hotel. Of these, only 150 were my friends, and the rest of the invitees were friends of my parents. It was a costume ball in the style of Georgette Heyer, the founder of the genre “ love story Regency era." It was wonderful! Especially men's suits- breeches with garters.

When you come to the ball, do you dance?

Not very often. But mazurka and Russian quadrille are a must!

Do you have an active social life? Besides balls, do you go to horse races, equestrian polo, or regatta?

To be honest, my social life is not that active. I went to the Royal Ascot only a few times in my life. I love the countryside, horses and hunting. I only come to London for special events. My daily life takes place in Provender, a village in Kent. I'm a typical villager. Proper country bumpkin. I love my dogs - they always follow me everywhere. The grandchildren say: “Grandma loves her dogs more than us and talks to them all the time.” This is true. I often feel better and more comfortable with animals than with people.

Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna and her self-portrait

Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna Romanova was the Emperor's youngest daughter Alexandra III and sister of Emperor Nicholas II. However, she is known not only for her noble origin, but also for her active charitable activities and artistic talent. She managed to avoid the terrible fate that befell her brother and his family - after the revolution she remained alive and went abroad. However, life in exile was far from cloudless: for some time paintings were her only means of livelihood.

On the left is Emperor Alexander III with his family. On the right – Olga Alexandrovna with her brother |

Sister of Emperor Nicholas II Olga Alexandrovna

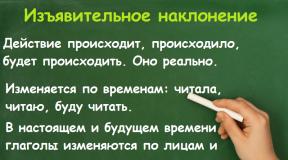

Olga Alexandrovna was born in 1882 and was the only child born purple - that is, born at a time when her father was already the reigning monarch. Olga showed her talent as an artist very early. She recalled: “Even during geography and arithmetic lessons, I was allowed to sit with a pencil in my hand because I listened better when I was drawing corn or wild flowers.” All children in the royal family were taught drawing, but only Olga Alexandrovna began painting professionally. Makovsky and Vinogradov became her teachers. The princess did not like the noisy metropolitan life and social entertainment, and instead of balls she preferred to spend time doing sketches.

V. Serov. Portrait of Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna, 1893

O. Kulikovskaya-Romanova. Self-portrait, 1920

From an early age, Olga Romanova was also involved in charity work: vernissages were held at the Gatchina Palace, at which her works and paintings by young artists were presented, and the money raised from their sale went to charitable causes. During the First World War, she equipped a hospital at her own expense, where she went to work as a simple nurse.

Grand Duchess in hospital

Grand Duchess among the wounded

At the age of 18, at the behest of her mother, Olga Alexandrovna married the Prince of Oldenburg. The marriage was not happy, since the husband, as they said then, “was not interested in ladies,” and besides, he was a drunkard and a gambler: in the very first years after the wedding, he lost a million gold rubles in gambling houses. The Grand Duchess admitted: “We lived with him under the same roof for 15 years, but we never became husband and wife; the Prince of Oldenburg and I were never in a marital relationship.”

The Grand Duchess and her first husband, the Prince of Oldenburg

2 years after the wedding, Olga Alexandrovna met officer Nikolai Kulikovsky. It was love at first sight. She wanted to divorce her husband, but the family was against it, and the lovers had to wait for the opportunity to marry for 13 long years. Their wedding took place in 1916. It was then that Olga Alexandrovna saw her brother, Emperor Nicholas II, for the last time.

Grand Duchess with her husband and children

When in 1918 the English King George V sent a warship for his aunt (Empress Maria Fedorovna), the Kulikovskys refused to go with them and went to Kuban, but two years later Olga Alexandrovna with her husband and sons still had to go to Denmark after mother. “I couldn’t believe that I was leaving my homeland forever. I was sure that I would return again,” Olga Alexandrovna recalled. “I had the feeling that my flight was a cowardly act, although I came to this decision for the sake of my young children. And yet I was constantly tormented by shame.”

O. Kulikovskaya-Romanova. Pond

O. Kulikovskaya-Romanova. House surrounded by blooming lilacs

O. Kulikovskaya-Romanova. Room in Kuswil

In the 1920-1940s. the paintings became a serious help and means of livelihood for the emperor’s sister. The Kulikovskys’ eldest son, Tikhon, recalled: “The Grand Duchess became the honorary chairman of a number of emigrant organizations, mainly charitable ones. At the same time, her artistic talent was appreciated and she began to exhibit her paintings not only in Denmark, but also in Paris, London, and Berlin. A significant portion of the proceeds went to charity. The icons painted by her did not go on sale - she only gave them as gifts.”

O. Kulikovskaya-Romanova. On the veranda

O. Kulikovskaya-Romanova. Cornflowers, daisies, poppies in a blue vase

O. Kulikovskaya-Romanova. Samovar

In emigration, her house became a real center of the Danish Russian colony, where the Grand Duchess's compatriots could turn for help, regardless of their political beliefs. After the war, this caused a negative reaction from the USSR; the Danish authorities demanded the extradition of the Grand Duchess, accusing her of aiding “enemies of the people.”

The Grand Duchess with her husband, Colonel Kulikovsky, and children

Therefore, in 1948, their family had to emigrate to Canada, where they spent their last years. There Olga Alexandrovna continued to paint, which she never gave up under any circumstances. Over the course of her life, she painted more than 2,000 paintings.

Left: O. Kulikovskaya-Romanova. Self-portrait. On the right is the artist at work

Grand Duchess with her husband

Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna died in 1960, at the age of 78, outliving her husband by 2 years and her older sister by 7 months.

In the summer of 2017, the St. Peter and Paul Cathedral in Montreal, of which I am a parishioner, celebrated its 110th anniversary. While in his book depository, I accidentally came across an album of photographs from the times Russian Empire, and in it - one portrait photograph that caught my attention. The sister of the last Russian Tsar, the passion-bearer Nikolai Alexandrovich Romanov, looked at me from there. Yes, it was a photo of Olga Alexandrovna Romanova, the Grand Duchess.

I became curious and began to carefully leaf through the archive. And I found in it a record that Olga Alexandrovna visited our cathedral, and lived just a few hours drive from Montreal in her last years.

I became curious and began to carefully leaf through the archive. And I found in it a record that Olga Alexandrovna visited our cathedral, and lived just a few hours drive from Montreal in her last years.

Having been interested in the history of the royal family for a long time, I decided to find everything that Russian Canada keeps about the life of the Grand Duchess and tell my reader about it. Perhaps some of what is written here will already be known, and some may be news to readers. In any case, today is my story about Olga Alexandrovna - from birth to funeral feast.

So, let's begin. Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna Romanova was born in the city of St. Petersburg on June 14, 1882. She was the youngest daughter of Emperor Alexander III and his wife Empress Maria Feodorovna, née a Danish princess. 101 salvos from the bastion of the Peter and Paul Fortress were fired in her honor, on her birthday. In addition, as time will tell and as she will later say about herself, she was the last porphyritic, or, as they also said, purplish-born member of the dynasty. The term applied only to sons and daughters born to the reigning monarch. Of all the children of Alexander III, only the youngest daughter Olga was porphyritic, since all her older brothers and sisters were born before their father became the Russian sovereign. All the children of her brother Nicholas II were porphyry, since they were born after their father’s accession to the throne. But we know the ending of their tragic destinies.

But let's return to Olga. Like all children of the reigning dynasty, her childhood was filled with luxury, wealth, happiness and carefreeness. From an early age, her family noticed her penchant for painting, and the best professors of this art were immediately hired to teach her the craft. It must be said that later this skill greatly helped her and her family, since her watercolors, which were in demand, were sold out well, and the proceeds from the fees helped feed Olga Alexandrovna’s family.

Little Olga loved horses very much. And they appear in large numbers in her first paintings. She associated everything with drawing, even mathematics.

An English governess was hired to raise the girl. It was this woman who became a friend, adviser, assistant, inspirer and comforter for the Grand Duchess.

Olga's closest friends were with her sister Ksenia, who was a little older than her. The girls played together, dressed up, rode horses and studied science. As fate would have it, both sisters will leave this world in the same year, just a few weeks apart.

The end of the century before last was not easy for the Romanov family. The threat of terrorism haunted the royal family. Therefore, children were kept away from the palace. The girls, Ksenia and Olga, were raised outside the city, in the Gatchina Palace. It was called a palace very conventionally, because the girls, accustomed to pampering and abundance, had to sleep practically on hard camp beds and eat oatmeal on the water. But in such a difficult time for the family, it was impossible to choose the conditions. And the girls resignedly accepted the living conditions offered to them.

And Olga realized very soon that these were not empty fears. The family went on vacation to the Caucasus. On the way back, their train derailed. The compartment in which the family was traveling was destroyed, and the collapsing roof almost fell on the sitting, frightened children. The Tsar-hero, thanks to his gigantic physique, managed to hold the collapsing roof. He subsequently paid for this with his health - the overload affected the sovereign’s kidneys, which gradually began to fail.

When Olga was 12 years old, her father passed away. Being very close to him, often communicating a lot with her father on various topics, she deeply experienced the loss.

With the beginning of the last century, the question arose about the marriage of Olga, who by that time had already turned 18 years old. But the mother, who loved her youngest daughter with some special love, never wanted her to go abroad. A prince was found for her in Russia. This was a distant relative of the Romanovs, a Russified German prince. At that time he was 32 years old. The wedding was played. But she did not bring happiness. The prince was not only an avid gambler who often lost large sums of money, but also a representative gay. In other words, he had absolutely no interest in women.

The princess was helped to overcome loneliness by painting and her little nieces, the daughters of Nicholas II, to whom Olga Alexandrovna fully devoted all her unspent love.

And in 1903, love knocked on her heart. At the parade in the Pavlovsk Palace, the Grand Duchess saw the captain of the Life Guards, Nikolai Kulikovsky. Olga's feelings turned out to be mutual, and the young people began to fight for their happiness.

She could not get a divorce for a very long time. But finally the sovereign took pity on his sister, and at the end of 1916 Olga, then working as a nurse in a hospital, finally received a letter from her brother about the dissolution of her marriage.

Later she will remember this moment and say that at that moment she will say the phrase:

“In fifteen years of marriage, I have never been in a marital relationship with my legal husband...”

The same letter contained the royal blessing for the wedding of Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna and Colonel Kulikovsky.

But 1917 was approaching, the terrible year of the Red Terror, the year that decided the fate of the Russian Empire. The year that signed the verdict of the entire royal dynasty.

Olga Alexandrovna gave birth to a son in August of this year, who was named Tikhon. The happiness of the young family was overshadowed by the terrible news of the death of the family of their brother-sovereign in 1918. And the Kulikovskys began to seriously think about leaving Russia, which was unsafe for them. Another year and a half later, their second son, Gury, is born.

Soon after the birth of their second son, Olga's family, bypassing Constantinople, Belgrade and Vienna, lands in Denmark.

Very often Olga Alexandrovna had moments of repentance for her cowardice, for her fear, for her flight... But the life of the children, so beloved, long-awaited and desired, was above all.

At first they lived in the royal palace of Amalienborg in Copenhagen together with the Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna and the Danish King Christian X, who was her nephew. Then they moved to a house bought for the empress, which was called Vidor Castle, on the outskirts of Copenhagen. After Maria Feodorovna died here in 1928, Olga Alexandrovna did not want to stay there. They first moved to a small farmhouse, where they remained for about 2 years. And when all the formalities with Maria Fedorovna’s inheritance were resolved and Olga Alexandrovna received her share, for the first time in her life she bought her own home, Knudsminde in Bollerule. In those days it was just a small village 24 kilometers from Copenhagen, but gradually Copenhagen expanded, and now this place, Bollerul, is already a suburb of Copenhagen, practically part of the city. While they lived there, Tikhon and Gury grew up and went to a regular Danish school. But in addition to this, they also went to a Russian school.

The days of everyday, seemingly unremarkable life flowed by. But thunder struck again in this family. Many years later, after the Second World War. The Grand Duchess was accused of helping Russian prisoners of war and was declared an enemy of the Soviet people.

Denmark did not want to extradite Olga Soviet Union, but at the same time she did not want to spoil diplomatic relations with him. Therefore, using their connections, the Danish royal family transported the Kulikovsky family to Canada.

So, at 66 years old, the Grand Duchess begins again new life. Together with her family, she bought a plot of land of 200 acres in the province of Ontario, as well as a small farm: cows and horses - Olga’s childhood love.

The neighbors simply called her Olga. And when one day a neighbor’s child asked her if it was true that she was a princess, Olga Alexandrovna replied:

"No. I am not a princess. I am the Russian Grand Duchess"

Every Sunday, the Kulikowski family visited the Cathedral of Christ the Savior in Toronto. Periodically leaving the city, Olga Alexandrovna visited other churches in different cities of Canada. In particular, she repeatedly visited our St. Peter and Paul Cathedral.

Living rather poorly, Olga Alexandrovna still sought funds to help her cathedral and painted icons for the iconostasis. A portrait of the Grand Duchess now hangs in the cathedral museum. Those few very elderly parishioners who were lucky enough to know her remember Olga Alexandrovna with great warmth and tenderness. The Sunday church school now bears her name.

The aging couple no longer had the strength to work on the farm, and they decided to sell it. And having sold, they moved to the suburbs of Toronto, where Olga Alexandrovna fully demonstrated her talent as an artist. She wrote about two thousand works. Exhibitions of her works were held many times.

Works belonging to the brush of Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna are now in the gallery of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II of Great Britain, in the collection of the Duke of Edinburgh, King Harald of Norway, in the Ballerup Museum, which is located in Denmark, as well as in private collections in the USA, Canada and Europe. Her paintings can also be seen in the residence of the Russian ambassador in Washington and in the New Tretyakov Gallery.

Finished my earthly path Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna in east Toronto, in a family of Russian emigrants, surrounded by former compatriots and a huge number of icons.

In 1958, she buried her husband, who was seriously ill and did not recover from his illness. And two years later, on the night of November 24-25, 1960, she herself went to the Lord. The princess was buried at the North York Russian Cemetery in Toronto next to her husband Nikolai Kulikovsky.

The eldest son Tikhon wrote a few days later in a letter to an old family friend that in recent days his mother had suffered greatly and had internal hemorrhage. And for the last two days she was unconscious. But before that, God vouchsafed the Grand Duchess to partake of the Holy Mysteries of Christ.

In a remote part of North York Cemetery you can see graves with inscriptions in Russian. You will definitely see a massive stone cross with Orthodox icon. This is the grave of Olga Alexandrovna Romanova, Nikolai Alexandrovich and Tikhon Nikolaevich Kulikovsky. Here they found their last refuge. The letters EIV under the cross mean: Her Imperial Highness.

The life of the Grand Duchess was full of humiliations, falls and disasters. But only the art of painting, the love for which she carried throughout her life, and faith in God, which deeply and firmly settled in her mind from childhood until her last days, saved her, did not allow her to break, helped her to survive, no matter what!

Eternal memory to you, Your Imperial Highness, Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna! And forgive all of us, whose ancestors, not knowing what they were doing, brought so much grief and blood to your family!

Pray for us before the Almighty! We need forgiveness...

In contact with

Oldenburg - German dukes and duchesses of the Holstein-Gottorp dynasty, immediate direct heirs of the Russian imperial family.

TO 19th century V Western Europe the dynasties of all the major states (with the exception of the Austrian Habsburgs, the German Hohenzollerns and the Italian Savoy dynasty) were foreign.

Dynasties of German origin ruled in Great Britain, Belgium, Portugal, and Bulgaria.

Representatives of the German Oldenburg dynasty belonged to the thrones in Denmark and Greece, Norway and Sweden, and in 1761 in Russia.

For the first time, the Oldenburg family became related to the House of Romanov during the time of Peter I, when his daughter Anna Petrovna married Duke Karl-Friedrich of Holstein - the nephew of the Swedish king Charles XII on the side of Sophia Hedwig's mother. This dynastic marriage forever linked with family ties the former worst enemies of Peter I and Charles XII, the dynasty of the Russian Romanov tsars and one of the branches of the Oldenburg family - the dynasty of Holstein-Gottorp dukes and duchesses.

From the marriage a son was born - Karl Peter Ulrich (Peter III), who was simultaneously the heir to the Swedish and Russian thrones, who was prepared from early childhood to inherit the Swedish throne, without paying due attention to becoming familiar with the language and customs of Russia.

In 1761, the Holstein-Gottorps, represented by Peter III, reigned in Russia and began to bear the name of the dynasty of Russian Romanov tsars and marry exclusively German princesses. But a year later they lost the throne.

From 1762 to 1796, Russia was ruled by the wife of Peter III, Catherine II (Princess Sophia-Frederica-Augustina of Zerbskaya), a representative of the Anhalt-Zerbian line of the ancient German Askani dynasty.

His Imperial Highness the Prince of Oldenburg - great-grandson of Emperor Paul I, member State Council, infantry general (adjutant general). On his birthday, he was enlisted as a warrant officer in the Preobrazhensky Regiment, in which he began military service in 1864. Awarded golden weapons and the Order of St. George. The son of Prince Peter Georgievich of Oldenburg - a well-known public and statesman, grandson of Prince George Petrovich, who moved to Russia in connection with his marriage to the daughter of Paul I, Ekaterina Pavlovna. In 1868, he repeated the story of his grandfather, again becoming related to the Romanovs, marrying Grand Duchess Evgenia Maximilyanovna, granddaughter of Nicholas I.

According to contemporaries, Alexander Petrovich was an active and energetic person. Busy with his military and state affairs, he spent most of his life in the capital and military campaigns, and Eugenia managed the affairs of the vast Ramon estate. In this his role was insignificant. With the name A.P. Oldenburgsky is associated with the founding of the Gagrinskaya climate station and the activities of the scientific and medical society. During the first imperialist war he was appointed Supreme Commander of the sanitary and evacuation unit of the Russian army. His residence was located in a special railway train, which traveled around the rear of the front.

He was a trustee of the St. Petersburg Imperial School of Law, the shelter of Prince Peter Georgievich of Oldenburg. In 1890, he opened the Imperial Institute of Experimental Medicine (now the I.P. Pavlov Institute). He was buried in Barritsa on the Atlantic coast.

The Grand Duchess is the youngest "porphyry" daughter of Emperor Alexander III, born of all 7 children during her father's reign, the sister of the last Russian Emperor Nicholas II. Since 1901, she has been married to Prince Peter of Oldenburg, the son of Princess Eugenie. After marriage, she lived on her Ramon estate “Olgino” (now the territory of a hospital). In 1902 -1908. improved the estate. She built a “palace” (now a maternity hospital), new houses, and outbuildings.

In 1902, she bought an estate in Starozhivotinny (former estate of the Olenins) in her name. She was the chief and honorary colonel of the 12th Tsar's Akhtyrsky Regiment, whose property warehouse was located in Ramon.

With the outbreak of the war with Germany, Prince Peter's adjutant, captain Nikolai Aleksandrovich Kulikovsky (1881-1959), was in the active army as part of the Akhtyrsky regiment. Olg; followed him and went to the front as a sister of mercy. She was awarded the St. George medal - one of the signs of the Order of St. George.

In 1916, the marriage of Olga and Peter was dissolved. In the same year, Olga married Kulikovsky, sold the Starozhivotinnovskoye estate and left Ramon.

The Kulikovsky couple ended up in Crimea. In 1919 they emigrated to Denmark. In 1948 they moved to Canada. Their sons Tikhon (1917-1993) and Gury (1919-1984) became officers of the Danish Guard.

In 1958, Olga Aleksandrovna Oldenburgskaya was widowed, and on November 24, 1960 she died in Toronto.

Oldenburgsky Peter gay porn Alexandrovich (1868-1924)

Oldenburgsky Peter gay porn Alexandrovich (1868-1924)

The prince, son of Alexander and Eugenia of Oldenburg, has been married to Olga Romanova since 1901. Major General of the infantry "Prince of Oldenburg Regiment". Was assigned to the Ministry of Agriculture. The 30-year-old prince founded an “experimental field” in Ramon; later it acquired a scientific character thanks to the estate manager, agronomist I.N. Klingen. In 1915 he was awarded the Arms of St. George for his participation in the First World War.

After the divorce from Olga in 1916, he became the owner of the Olgino estate. In 1917 he joined the Socialist Revolutionary Party. At the end of 1917 he emigrated abroad to France. He died of transient consumption at the age of 56, and was buried in Cannes in the dungeon of the Russian Church of the Archangel Michael.

Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna. Princess of Oldenburg. Olga Romanova-Kulikovskaya. This is all about the same woman: the daughter of Alexander III, the sister of Nicholas II, the wife of Prince Oldenburg, the beloved wife of a simple officer Nikolai Kulikovsky, the artist Olga Romanova-Kulikovskaya.

Read how sublimely and respectfully they wrote about Olga Alexandrovna, the younger sister of the last Russian emperor. This is not flattery before a high title and royal kinship. This is the respect and gratitude of the people for her good deeds. Charity is the duty of the royal children to their people, and they were taught to give time, energy and money to this from early childhood. The royal children should have - and set an example of caring for those who needed help, especially since, having entered the new century, Europe immediately entered into World War, and Russia had to support its allies before the first attempt in the new century to take over the world.

“The younger sister of the last Russian Emperor Nicholas II, Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna, was a talented professional artist.

Olga Alexandrovna is the youngest daughter of Emperor Alexander III and Empress Maria Feodorovna, née Princess Dagmar of Denmark. She was born in 1882. Unlike her older brothers, including the future Emperor Nicholas II, and sister, Grand Duchess Olga was called the Purple-born, since she was born when her father had already become the reigning monarch. The galleries of the huge Gatchina Palace, where she spent her childhood, housed unique collections of works of art from all over the world. Every corner in Gatchina spoke of Russia's great past. Grand Duchess Olga most conscientiously studied the history of Russia and from a young age absorbed an inescapable love for her fatherland.

Under Emperor Alexander III, Russia enjoyed peace along the perimeter of all borders, and the home life of the royal family was peaceful and happy. Grand Duchess Olga adored her father, a powerful, confident ruler, and in the family circle cheerful, affectionate and so cozy. The untimely death of Alexander III in 1894 became the first cruel blow of fate for 12-year-old Olga. Very early at the Grand Duchess's  Olga's talent as an artist began to emerge. Even during geography and arithmetic lessons, she was allowed to sit with a pencil in her hand, since she listened better when drawing corn or wild flowers. Outstanding artists became her painting teachers: academician Karl Lemokh, later Vladimir Makovsky, landscape painters Zhukovsky and Vinogradov. In memory of her other teacher, academician Konstantin Kryzhitsky, Olga Alexandrovna founded the Society for Helping Needy Artists in 1912, and organized charity exhibitions in her palace on Sergievskaya Street - sales of her own paintings.

Olga's talent as an artist began to emerge. Even during geography and arithmetic lessons, she was allowed to sit with a pencil in her hand, since she listened better when drawing corn or wild flowers. Outstanding artists became her painting teachers: academician Karl Lemokh, later Vladimir Makovsky, landscape painters Zhukovsky and Vinogradov. In memory of her other teacher, academician Konstantin Kryzhitsky, Olga Alexandrovna founded the Society for Helping Needy Artists in 1912, and organized charity exhibitions in her palace on Sergievskaya Street - sales of her own paintings.

Her soul was open to the beauty of nature and selfless help to people. Since childhood, the Grand Duchess has patronized many charitable institutions and organizations. Before the revolution, the august artist was known throughout Russia - charity cards with her watercolors, published mainly by the Community of St. Eugenia of the Red Cross, sold in huge quantities.”

A somewhat popular portrait, isn’t it? But if you put aside the old-fashioned turns of phrase, all this is true, because the life of the royal family was always in plain sight. Everyone knew about the Grand Duchess’s unhappy marriage. This was not a fairy tale, although at the turn of the 20th century, girls, free from debt to the royal family, chose their husbands themselves, most often by inclination. Of course, both class and  mercantile interests of the family, although misalliances increasingly occurred. But the royal children were instilled from childhood that they live for higher, state interests; feelings did not play a role here. But still, the saying “If you endure it, you will fall in love!” often came into play, sometimes bringing very good results. Olga's older brother married very successfully and eventually became happy in his marriage. But Olga was not so lucky. At the age of 19, by the will of her mother, Olga Alexandrovna married Prince Peter of Oldenburg. One could not even think about family happiness with this passionate player. Memoirists testify that the prince spent his wedding night at the gaming table. It is not surprising that he subsequently squandered a million rubles, which Olga inherited from her brother George. Where is the happiness here? After all, it takes two to build it...

mercantile interests of the family, although misalliances increasingly occurred. But the royal children were instilled from childhood that they live for higher, state interests; feelings did not play a role here. But still, the saying “If you endure it, you will fall in love!” often came into play, sometimes bringing very good results. Olga's older brother married very successfully and eventually became happy in his marriage. But Olga was not so lucky. At the age of 19, by the will of her mother, Olga Alexandrovna married Prince Peter of Oldenburg. One could not even think about family happiness with this passionate player. Memoirists testify that the prince spent his wedding night at the gaming table. It is not surprising that he subsequently squandered a million rubles, which Olga inherited from her brother George. Where is the happiness here? After all, it takes two to build it...

But then fate gave Olga Alexandrovna great love and a lifelong “knight” Nikolai Alexandrovich Kulikovsky. The Grand Duchess had to wait 7 years for her happiness with an officer, a man not of a royal family, until by decree of Nicholas II her marriage to the Prince of Oldenburg was finalized.

But then fate gave Olga Alexandrovna great love and a lifelong “knight” Nikolai Alexandrovich Kulikovsky. The Grand Duchess had to wait 7 years for her happiness with an officer, a man not of a royal family, until by decree of Nicholas II her marriage to the Prince of Oldenburg was finalized.  cancelled. The wedding took place in 1916 in Kyiv, in the church at the hospital, which Olga Alexandrovna headed and equipped at her own expense during the First World War.

cancelled. The wedding took place in 1916 in Kyiv, in the church at the hospital, which Olga Alexandrovna headed and equipped at her own expense during the First World War.

After the February Revolution, the Dowager Empress with both daughters and their families was in Crimea, where Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna gave birth to her first child in August 1917, baptized by Tikhon. In Crimea, they were all prisoners and were actually sentenced to death. In November 1918, the whites came to Crimea, and with them the allies. The English King George V sent for Maria Feodorovna, who was his aunt, the warship H.M.S. Marlboro. The Dowager Empress chose to settle at the Danish royal court; a year later she was joined by her youngest daughter Olga Alexandrovna with her husband and two sons.

“After the death of the Empress mother in 1928, Olga Alexandrovna’s family could only count on their own, very modest funds. The couple purchased a farm near Copenhagen with a cozy house, which became the center of the Russian monarchical colony in Denmark. At the same time, the artistic talent of the Grand Duchess was truly appreciated She worked a lot and exhibited her paintings not only in Denmark, but also in Paris, London, and Berlin. A significant part of the proceeds from the sale of paintings, as before, went to charity. Only the icons she painted were donated for Christ’s sake. , apparently never signed. Fragments of the iconostasis by her have been preserved in the Cathedral of Christ the Savior in Toronto, Canada.

The reason for the Grand Duchess's family moving to Canada in 1948 was a USSR government note to the Danish government accusing Olga Alexandrovna of helping “enemies of the people.” All years of occupation  Denmark by the Germans and after the liberation of the country by the Allies, the Grand Duchess helped all Russian exiles without exception, among whom were “defectors.” The last decade of the Grand Duchess's life was spent in a modest house on the outskirts of Toronto. She continued to paint. The fruits of her creativity made a significant contribution to the family budget. Her professionalism as an artist is evidenced by the author’s copies of the subjects that were especially loved by admirers of her talent, which she made to order. Olga Alexandrovna preferred to send her works to Europe rather than exhibit in Canada, where it was necessary to create some kind of public “publicity” around the artist’s name. However, as Olga Alexandrovna’s circle of Canadian acquaintances expanded, so did her authority as an artist, now on both sides of the ocean.”

Denmark by the Germans and after the liberation of the country by the Allies, the Grand Duchess helped all Russian exiles without exception, among whom were “defectors.” The last decade of the Grand Duchess's life was spent in a modest house on the outskirts of Toronto. She continued to paint. The fruits of her creativity made a significant contribution to the family budget. Her professionalism as an artist is evidenced by the author’s copies of the subjects that were especially loved by admirers of her talent, which she made to order. Olga Alexandrovna preferred to send her works to Europe rather than exhibit in Canada, where it was necessary to create some kind of public “publicity” around the artist’s name. However, as Olga Alexandrovna’s circle of Canadian acquaintances expanded, so did her authority as an artist, now on both sides of the ocean.”

A large exhibition of Olga Alexandrovna’s works was in the Tsaritsyno Museum, presented by her daughter-in-law of the Grand Duchess, Olga Nikolaevna Romanova-Kulikovskaya.

photo from the exhibition

photo from the exhibition

“Thus, Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna, infinitely devoted to Russia until the end of her days, but did not have the opportunity to set foot on native land, returns today with his creativity."

Found the material online Lenny. Processing the category editor.

Galla: Lenny, thank you, a very interesting and beautiful story!!!

Indeed, an amazingly talented artist and an extraordinary woman with an amazing destiny!!! First birth at 35 years old!!! While!!! And even in 1917!!!

Spate: Lenny, thank you very much for the article - very interesting! And what pictures... I especially liked the last one - it’s so cozy, tender, bright, summery... And the girl seems about to take off and run off to play. By the way, soon we will have a theme of female artists, I hope you will prepare something interesting for us?

Snowy garden

Old fence

M de R.

Read also...

- M. V. Koltunova language and business communication. Language and business communication Etiquette and protocol of business communication

- The Last of the Mohicans Fenimore Cooper The Last of the Mohicans

- Descriptive phrase for the word flower

- Mikhail Zoshchenko - Don't lie: Fairy tale Don't lie Zoshchenko genre